By Maya Shetty, BS

In an era where time is a precious commodity, individuals are constantly seeking efficient ways to achieve their fitness goals. Amidst this quest, high-intensity interval training (HIIT), which is a type of interval training (IT), has gained popularity among fitness enthusiasts due to its ability to yield significant health benefits in a short amount of time.

“I recommend interval training for people who are busy but still want to get fit, because it gets great results in a fraction of the amount of time compared to more traditional cardio workouts. Interval training can be a powerful tool in a well-rounded fitness plan,” says Anne Friedlander, PhD, exercise physiologist and assistant director of Stanford Lifestyle Medicine.

What is Interval Training?

Interval training (IT) was originally defined in 1973 as “intermittent periods of intense exercise separated by periods of recovery.” HIIT stands for high-intensity interval training, which has become the most popular form of IT in recent years. This back-and-forth between physical effort and rest is effective because it challenges the body without causing total exhaustion. IT can encompass various exercise modalities, including cardio, explosive movements with weights, and bodyweight exercises, as long as the period of intense exercise strenuously stimulates the body.

Despite IT’s recent surge in popularity in the US, European runners in the 1950s commonly used this training method, including long-distance runner Emil Zatopekl from the Czech Republic. Zatopekl’s success in the 1952 Olympics is believed to have ignited the widespread adoption of IT across various sports disciplines.

In 2006, a study conducted by Canadian researcher Martin Gibala sparked enthusiasm for IT to improve fitness, not only among athletes, but for the general population as well. The Gibala paper found that even though study participants trained eight hours less over a two-week period, their IT protocol (four to six, 30-second cycling intervals at supramaximal effort with a four-minute recovery) yielded similar fitness and muscle improvements compared to their moderate intensity continuous training (MICT) protocol (90 to 120 minutes of continuous cycling). Adaptations included better time-trial performance (time to complete a set amount of work on a bike), increased oxidative capacity (ability of muscles to use oxygen), buffering capacity (ability to handle acidity during exercise), and glycogen content (more energy stores in the muscles).

Since this pivotal 2006 study, researchers have studied IT protocols extensively and found, when compared to MICT, participants can elicit the same or greater benefits in mitochondrial density, aerobic capacity, metabolic health, insulin sensitivity, body composition, heart disease progression, and markers of genetic age.

In the last two decades, IT has evolved into various types, such as HIIT and sprint interval training (SIT), which have differences in physiological and psychological responses depending on the duration and intensity of the exercise protocol. Many use the classifications outlined in a 2014 review paper, which defines HIIT as a training protocol that requires “near maximal” effort, eliciting 80 to 100 percent of maximal heart rate (HRmax) or aerobic capacity (VO2max). (A very rough estimate of your max heart rate can be obtained using the formula: 220 – your age.) SIT, on the other hand, is classified as a training protocol that requires “supramaximal” or all-out effort, using at least 100 percent of one’s maximal aerobic capacity.

“No matter what your starting fitness level, adding intensity to your workouts can help you achieve your health and fitness goals,” says Dr. Friedlander, adjunct professor in the Stanford Program in Human Biology. “There are many different protocols out there, but the key element is pushing yourself hard for short bursts of time separated by recovery periods. Those bursts of hard work will jump start beneficial adaptations in your physiology and metabolism.”

What are the Benefits of Interval Training?

c

Muscle Health

The 2006 Gibala paper was the first to reveal how SIT has nearly the same effects on skeletal muscle adaptations as MICT despite significantly less training time and workload. Additional research has shown that a single session of HIIT or SIT increases mitochondrial biogenesis (the process through which muscle cells increase the number and functional capacity of mitochondria), and repeated sessions lead to overall increases in mitochondrial density. Mitochondrial biogenesis plays a crucial role in energy production, metabolic regulation, and overall cellular health. It is important to have healthy and functioning mitochondria to maintain muscle health and decrease the risk of sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss).

Research suggests, in the short-term, that the intensity and interval nature of HIIT and SIT increases mitochondrial biogenesis more than MICT, even when performed for less time and at an equal or less total amount of work. Therefore, incorporating interval training into your lifelong exercise routine (such as adding short bouts of running to your daily walks) will help improve your short-term, and possibly long-term, muscle function.

Body Composition

A meta-analysis that included individuals of all ages and health statuses found SIT protocols were more time efficient than MICT and HIIT in decreasing body fat.

Another meta-analysis, looking at studies including only overweight individuals, found HIIT protocols were more time efficient than MICT in reducing whole-body fat mass and waist circumference. Here, the researchers found that running protocols were more effective than cycling protocols for decreasing body fat, potentially because running uses more muscles throughout the body, which leads to greater energy expenditure.

Cardiovascular Health

A wealth of research since 2006 has consistently demonstrated that IT provides superior improvements in markers of cardiovascular health, cardiometabolic health, and mitigates the risk of heart disease progression more efficiently compared to MICT.

Cardiorespiratory health: VO2max (the body’s maximum rate of oxygen consumption) is a common indicator of cardiorespiratory health. Individuals with a higher VO2max tend to have better overall physical fitness, improved lung function, stronger heart muscles, and enhanced oxygen delivery to the body’s tissues.

A meta-analysis determined that both HIIT and SIT protocols are more efficient than MICT regarding the improvement of VO2max (cardiorespiratory fitness). One study found that SIT increased VO2max to the same extent as MICT, but in one-fifth of the time.

The duration of intervals may also have an impact on VO2max. A comprehensive meta-analysis revealed that IT protocols with longer intervals of intensity (three-to-five minutes) yielded greater improvements in VO2max compared to shorter interval protocols performed for the same total amount of time.

Cardiometabolic health: Interval training is also a powerful tool for improving markers of cardiometabolic health, such as insulin sensitivity and insulin resistance.

A meta-analysis found a variety of IT protocols were superior to MICT in improving insulin resistance, lowering blood glucose levels, and decreasing body weight. The analysis examined various IT protocols, including HIIT and SIT, with a range of two-to-sixty intervals, durations from four seconds to five minutes, and both maximal and supramaximal intensities. Some studies were conducted in lab settings with stationary bikes or treadmills, while others were outdoors on tracks or trails.

“Although research has confirmed that IT is a more time-efficient method than MICT for improved muscle, cardiorespiratory, and cardiometabolic health in the short-term, more research is needed to confirm that those superior benefits continue in the long-term,” says Dr. Friedlander. “As with many aspects of life, balance is key. Therefore, integrating IT into a well-rounded fitness plan is probably healthier and more advantageous in the long-term than doing IT as your only training method.”

Brain Health

Research suggests that regular physical activity can mitigate age-related volume loss in brain regions associated with memory by improving blood flow to the brain and increasing the maintenance and production of neurons.

One study suggests that intense exercise, like HIIT and SIT, can enhance memory in older adults more effectively than MICT protocols. Participants in this study underwent a HIIT protocol, which included four-minute intervals of running on a five percent incline, interspersed with three-minute recovery periods of walking. They performed this protocol three times per week for a total of 12 weeks, resulting in improved memory performance significantly more than MICT or stretching protocols.

Another study found that young adults had more memory improvements following HIIT sessions (two-minute intense intervals interspersed with two-minute recovery periods) than MICT training sessions. The underlying mechanisms behind these improvements in memory are unknown, but the study did find a correlation between memory improvements and the release of blood lactate following exercise.

During exercise, the chemical lactate travels via the bloodstream to the brain and it is hypothesized that lactate promotes the creation of new cells and blood vessels, thus improving brain function. Higher exercise intensity leads to higher lactate production, resulting in increased levels of lactate in the bloodstream.

It has also been hypothesized that exercise induces the release of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that plays an essential role in the health and function of our brain cells. BDNF can be thought of as a “brain fertilizer” that helps neurons grow, survive, and communicate with each other.

Research studies have determined the majority of BDNF is produced in the brain, but other parts of the body, such as skeletal muscle and blood vessels, can also produce BDNF when stimulated by exercise. The previous studies in older and younger adults found that both HIIT and MICT protocols increased BDNF in the bloodstream immediately following exercise.

“Whether your goals relate to health, performance, or body composition changes, research has shown time and time again that IT protocols provide a time efficient way to target those goals,” says Dr. Friedlander. “However, you shouldn’t do IT every day as the intense nature of the activity requires sufficient recovery time, so as not to wear yourself down.”

Types of Interval Training Workouts

Since it is not recommended to do IT every day, one can integrate one of the following IT workouts a couple of times into their weekly exercise regimen.

Here are a few IT training methods that can be modified to any fitness level:

Martin Gibala General Recommendations: Gibala, one of the most notable IT researchers, recommends three sessions of HIIT or SIT exercise per week. Intervals should be between one and four minutes and the entire workout, including rest, should be between 20 to 30 minutes.

Fartlek: Fartlek is a running training method that involves alternating between faster-paced running and slower recovery periods, which can be at an easy or moderate pace. Fartlek training is flexible and can be adjusted based on the terrain, fitness level, and desired outcomes.

Tabata: Tabata involves 20 seconds of all-out intense exercise followed by 10 seconds of rest, repeated for a total of eight rounds (four minutes total). Tabata workouts can be customized for various training modalities that include stationary bikes, sprints, or body weight exercises.

4×4 Interval Training: In 4×4 IT, one performs four sets of intense intervals, with each set consisting of a four-minute, high-intensity exercise followed by a three-minute recovery period. This protocol should last a total of 28 minutes with each set lasting seven minutes (four minutes of activity and three minutes of recovery).

10-20-30: 10-20-30 training involves intervals of an aerobic exercise that alternates interval times. The workout consists of repeating cycles of 30 seconds of low-intensity exercise, followed by 20 seconds of moderate-intensity exercise, and finally, 10 seconds of high-intensity exercise. This pattern is repeated for several intervals, typically for a total of four to five minutes.

“Whatever your fitness level, incorporating safe and balanced interval training into your exercise routine can improve several aspects of your health and fitness. This is even true as we get older,” says Dr. Friedlander. “As we age, we tend to stay in our comfort zones, but sometimes it is good to push ourselves to keep our maximum capacity higher. This allows all of our other activities of daily life to feel easier. It can help us live life to the fullest into our later years.”

“If you’re new to interval training, start by adding a few bursts of running or hill climbing into your daily walk or find the stairs in your building at work and do three rounds of vigorously climbing while slowing descending them,” says Dr. Friedlander. “Regardless of your age or fitness level, we encourage you to embrace the challenge of IT and experience its whole-body health benefits!”

By Maya Shetty, BS

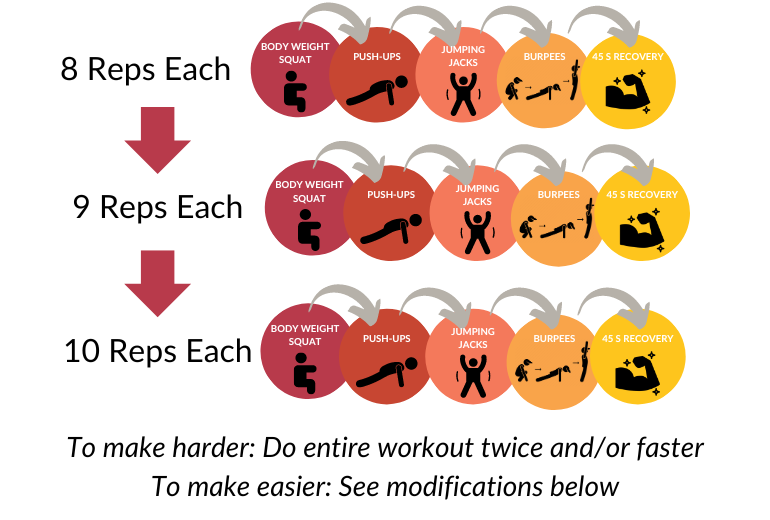

Warm up: Perform five reps of the exercises in the graphic at a slow and controlled pace, modifying as needed, and repeat.

Warm up: Perform five reps of the exercises in the graphic at a slow and controlled pace, modifying as needed, and repeat.