Impact of the Ketogenic Diet on Mental Health

By Claire Paul

Can food really impact your mood? Nutritional psychiatry, the use of food interventions as a form of mental health treatment, has gained popularity in recent years. While there’s an overwhelming amount of dietary suggestions out there, it is worth noting a 2023 comprehensive review assessing the relationship of the Ketogenic diet with neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases. Although not recommended for everyone, the ketogenic diet may be one avenue for improving mental health through food. Moreover some principles of the ketogenic diet may be applied more broadly.

Dr. Shebani Sethi, founding director of the Metabolic Psychiatry Clinical Program at Stanford University explains that, “While the ketogenic diet may not be suitable for everyone, its underlying principles of reducing neuroinflammation and supporting cognitive function can be integrated into everyday habits.”

What is the Ketogenic Diet?

While popularized in the media as another low-carb weight loss fad, the ketogenic diet was actually developed initially as a treatment for epileptic patients. It has been used to treat epilepsy since 500 BC but was more popularized by physicians in the 1920s. The diet focuses on fats being the primary source of fuel instead of carbohydrates; however, the ratio of macronutrients is dependent on the use of the diet. A 4:1 fat-to-carbohydrate ratio is typically used in clinical treatment, whereas a 3:1 ratio will be suggested for those who require higher amounts of protein or carbohydrate intake. While many different iterations of this diet exist, the Mentzelou et al 2023 review defined it as follows: 1 gram of protein per kilogram of body weight, 10-15 grams of carbohydrates, and the remainder of daily caloric intake from fat. The ultimate goal of the diet is to induce the production of ketones, a chemical stored in the liver to break down fat. The state of ketosis modifies metabolic pathways and has been associated with the reduction of oxidative damage and inflammation regulation.

What did they find?

The Mentzelou et al 2023 review contains a comprehensive search of existing peer-reviewed journal papers published between 2000 and 2023. Notably, the authors only included studies based on the classical ketogenic diet, defined above, and for in vivo studies, only research on Caucasian individuals was included. With this inclusion criterion in mind, the authors still found a mountain of evidence, 101 articles to be exact. Interestingly, they excluded over 300 articles because they didn’t fit the classical ketogenic diet criteria, which goes to show much research is actually on this “fad” diet. After collating the data the articles were categorized into in vitro and in vivo research.

In vitro

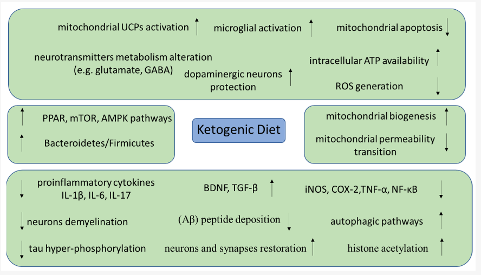

In general, in vitro (cell culture/mechanism studies) research indicates that ketogenic diets can help to increase mitochondrial health. The authors indicate that this can happen in a few different ways, such as decreasing mitochondrial apoptosis (i.e., death), increasing mitochondrial biogenesis (i.e., birth), and improving the function of existing mitochondria. If you remember back to high school biology class the mitochondria are the “powerhouse of the cell” so having more of them, having them not prematurely die, and having them work better, all add up to a more efficient system. Interestingly , the ketogenic diet is postulated to help in other areas as well, such as the microbiome and synapse myelination. A summary of the molecular mechanisms is shown in Figure 1.

Figure from Mentzelou et al. (2023), pg 5.

In vivo

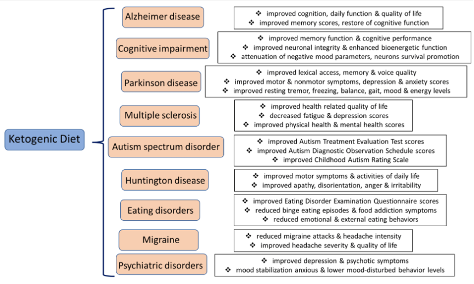

The study looked at the clinical implications of the Ketogenic diet for the treatment and management of neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases. In a study without 31 individuals with psychiatric disease (major depression, bipolar disease, schizoaffective disease) who followed the ketogenic diet between 6 and 248, there was a considerable link between improvements in depressive and psychotic symptomatology. A study also examined the effects of the Ketogenic diet on Alzheimer’s disease. After following the diet for 16 weeks, mice showed lower amyloid plaque accumulation and thus decreased neuroinflammation. A study of 23 individuals with mild cognitive impairment also looked at the relationship between following the Ketogenic diet and their symptoms. After following the diet for 6 weeks, they displayed improved memory function. Figure 3 from the study displays the results of the Ketogenic Diet for each neurodegenerative and psychiatric disease in the specific study.

Figure from Mentzelou et al. (2023), pg 8.

Another notable case study examined long-term Ketosis associated with considerable mood stabilization. A 70-year-old women experienced therapy-tolerant schizophrenia for 53 years and implemented the Ketogenic diet. She was able to stay off all psychiatric medications for 11 years and her symptoms subsided.

What can you do?

The principles of the KD can still be implemented by individuals looking to reduce neuroinflammation, diversify the microbiota, and improve overall cognitive functioning.

- Reduce Processed Carbohydrate intake

- Increase Healthy Fats, especially omega-3 fats

- Consume moderate amounts of protein

- Incorporate a variety of fiber-rich plants into the diet

While the ketogenic diet is just one avenue of doing such, the principles listed above are all tied to improved mental health. While food is not the sole determinant of mood, there’s certainly something to be said about its impact on mental health and well-being.

Precautions and Things to Note

It’s important to be aware of many limitations to the findings and potential side effects of the Ketogenic diet. While these are individual studies, clinical evidence remains scarce due to their short term, lack of a control group, or large dropout rates. Though all meta-analyses support the efficiency of the ketogenic diet as a treatment for epilepsy, further studies need to be implemented to draw this conclusion for other mental health disorders. Certain side effects are also necessary to be aware of, including the phenomenon of the “keto flu,” a sickness which typically subsides after a few days. Additionally, maintenance of the diet can be challenging which is why it’s necessary to follow the protocol in accordance to one’s individual needs.

Dr. Shebani Sethi notes that, “Optimizing brain health goes beyond symptom management; it requires addressing the metabolic underpinnings of psychiatric conditions. The ketogenic diet, with its emphasis on enhancing mitochondrial function and reducing oxidative stress, aligns with the goals of promoting mental health and vitality.”

However, it’s necessary that “As we continue to explore the relationship between nutrition, metabolism, and mental health, it’s essential to approach lifestyle changes with caution and under the guidance of healthcare professionals.”

As always, before starting any new diet to treat a specific symptom or disorder, it is imperative to first talk with your healthcare provider.