Impaired 24-h activity patterns are associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and cognitive decline

/in Team Member Publications /by Maya ShettyThe Association Between Well-Being and Empathy in Medical Residents: A Cross-Sectional Survey

/in Team Member Publications /by Maya ShettyThe Healthspan Project: A Retrospective Pilot of Biomarkers and Biometric Outcomes after a 6-Month Multi-Modal Wellness Intervention

/in Team Member Publications /by Maya ShettyThere is a knowledge gap around menstruation in NZ – and this puts people at risk – The Conversation

/in Team Members in the News /by Maya ShettyDr. Stacy Sims highlights a critical gap in understanding among New Zealand’s youth, including girls, young women, and nonbinary individuals who menstruate, regarding menstruation. This shortfall in knowledge significantly impacts their health and well-being, underscoring the urgent need for improved education and resources in this area.

More people are getting injured playing pickleball. Here’s what’s behind it – San Francisco Chronicle

/in Team Members in the News /by Maya ShettyStanford Lifestyle Medicine Director, Dr. Michael Fredericson, discusses the rise in pickleball injuries in recent years.

Feeling Overwhelmed? Try Tallying Your Tiny Wins. – The New York Times

/in Team Members in the News /by Maya ShettyDr. BJ Fogg, Stanford Lifestyle Medicine Research and Implementation Specialist, speaks with the New York on how taking stock of small achievements can keep you motivated when times are tough.

Impact of the Ketogenic Diet on Mental Health

/in Student Blogs /by Maya ShettyBy Claire Paul

Can food really impact your mood? Nutritional psychiatry, the use of food interventions as a form of mental health treatment, has gained popularity in recent years. While there’s an overwhelming amount of dietary suggestions out there, it is worth noting a 2023 comprehensive review assessing the relationship of the Ketogenic diet with neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases. Although not recommended for everyone, the ketogenic diet may be one avenue for improving mental health through food. Moreover some principles of the ketogenic diet may be applied more broadly.

Dr. Shebani Sethi, founding director of the Metabolic Psychiatry Clinical Program at Stanford University explains that, “While the ketogenic diet may not be suitable for everyone, its underlying principles of reducing neuroinflammation and supporting cognitive function can be integrated into everyday habits.”

What is the Ketogenic Diet?

While popularized in the media as another low-carb weight loss fad, the ketogenic diet was actually developed initially as a treatment for epileptic patients. It has been used to treat epilepsy since 500 BC but was more popularized by physicians in the 1920s. The diet focuses on fats being the primary source of fuel instead of carbohydrates; however, the ratio of macronutrients is dependent on the use of the diet. A 4:1 fat-to-carbohydrate ratio is typically used in clinical treatment, whereas a 3:1 ratio will be suggested for those who require higher amounts of protein or carbohydrate intake. While many different iterations of this diet exist, the Mentzelou et al 2023 review defined it as follows: 1 gram of protein per kilogram of body weight, 10-15 grams of carbohydrates, and the remainder of daily caloric intake from fat. The ultimate goal of the diet is to induce the production of ketones, a chemical stored in the liver to break down fat. The state of ketosis modifies metabolic pathways and has been associated with the reduction of oxidative damage and inflammation regulation.

What did they find?

The Mentzelou et al 2023 review contains a comprehensive search of existing peer-reviewed journal papers published between 2000 and 2023. Notably, the authors only included studies based on the classical ketogenic diet, defined above, and for in vivo studies, only research on Caucasian individuals was included. With this inclusion criterion in mind, the authors still found a mountain of evidence, 101 articles to be exact. Interestingly, they excluded over 300 articles because they didn’t fit the classical ketogenic diet criteria, which goes to show much research is actually on this “fad” diet. After collating the data the articles were categorized into in vitro and in vivo research.

In vitro

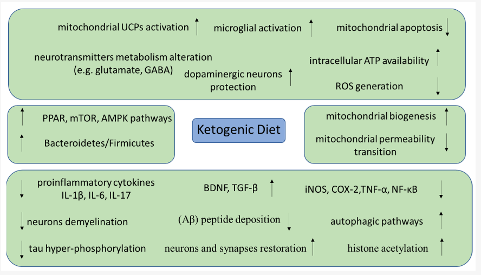

In general, in vitro (cell culture/mechanism studies) research indicates that ketogenic diets can help to increase mitochondrial health. The authors indicate that this can happen in a few different ways, such as decreasing mitochondrial apoptosis (i.e., death), increasing mitochondrial biogenesis (i.e., birth), and improving the function of existing mitochondria. If you remember back to high school biology class the mitochondria are the “powerhouse of the cell” so having more of them, having them not prematurely die, and having them work better, all add up to a more efficient system. Interestingly , the ketogenic diet is postulated to help in other areas as well, such as the microbiome and synapse myelination. A summary of the molecular mechanisms is shown in Figure 1.

Figure from Mentzelou et al. (2023), pg 5.

In vivo

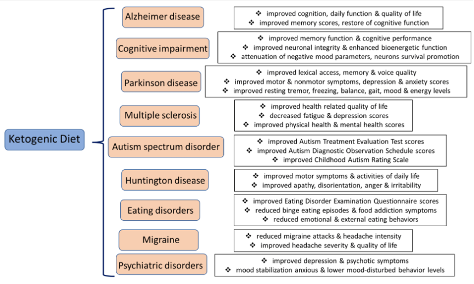

The study looked at the clinical implications of the Ketogenic diet for the treatment and management of neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases. In a study without 31 individuals with psychiatric disease (major depression, bipolar disease, schizoaffective disease) who followed the ketogenic diet between 6 and 248, there was a considerable link between improvements in depressive and psychotic symptomatology. A study also examined the effects of the Ketogenic diet on Alzheimer’s disease. After following the diet for 16 weeks, mice showed lower amyloid plaque accumulation and thus decreased neuroinflammation. A study of 23 individuals with mild cognitive impairment also looked at the relationship between following the Ketogenic diet and their symptoms. After following the diet for 6 weeks, they displayed improved memory function. Figure 3 from the study displays the results of the Ketogenic Diet for each neurodegenerative and psychiatric disease in the specific study.

Figure from Mentzelou et al. (2023), pg 8.

Another notable case study examined long-term Ketosis associated with considerable mood stabilization. A 70-year-old women experienced therapy-tolerant schizophrenia for 53 years and implemented the Ketogenic diet. She was able to stay off all psychiatric medications for 11 years and her symptoms subsided.

What can you do?

The principles of the KD can still be implemented by individuals looking to reduce neuroinflammation, diversify the microbiota, and improve overall cognitive functioning.

- Reduce Processed Carbohydrate intake

- Increase Healthy Fats, especially omega-3 fats

- Consume moderate amounts of protein

- Incorporate a variety of fiber-rich plants into the diet

While the ketogenic diet is just one avenue of doing such, the principles listed above are all tied to improved mental health. While food is not the sole determinant of mood, there’s certainly something to be said about its impact on mental health and well-being.

Precautions and Things to Note

It’s important to be aware of many limitations to the findings and potential side effects of the Ketogenic diet. While these are individual studies, clinical evidence remains scarce due to their short term, lack of a control group, or large dropout rates. Though all meta-analyses support the efficiency of the ketogenic diet as a treatment for epilepsy, further studies need to be implemented to draw this conclusion for other mental health disorders. Certain side effects are also necessary to be aware of, including the phenomenon of the “keto flu,” a sickness which typically subsides after a few days. Additionally, maintenance of the diet can be challenging which is why it’s necessary to follow the protocol in accordance to one’s individual needs.

Dr. Shebani Sethi notes that, “Optimizing brain health goes beyond symptom management; it requires addressing the metabolic underpinnings of psychiatric conditions. The ketogenic diet, with its emphasis on enhancing mitochondrial function and reducing oxidative stress, aligns with the goals of promoting mental health and vitality.”

However, it’s necessary that “As we continue to explore the relationship between nutrition, metabolism, and mental health, it’s essential to approach lifestyle changes with caution and under the guidance of healthcare professionals.”

As always, before starting any new diet to treat a specific symptom or disorder, it is imperative to first talk with your healthcare provider.

A Step Up to Health: The Power of Stairs

/in Student Blogs /by Maya ShettyBy Anya Higashionna and Jonanne Talebloo

With the increasing automation of the world around us, Levi Frehlich MSc PhD ©, emphasizes, “We are learning more and more that a sedentary behavior independent of your activity levels can have a profound influence on your health. The environment can be used to break up sedentary behavior and utilizing stairs can be a “great first step.”

How many times a week are you faced with the decision: stairs or elevator? What goes through your head and influences your decision? Maybe you are trying to weigh out the benefits of being healthy versus “saving time” with an elevator. One counter to think about is walking up an escalator – a third option that is both faster and healthier! The contents of this post may change the way you think during this practically daily decision we are expected to make.

Furthermore, it is essential to understand that this question may be more important than we initially perceived. With heart disease being the most expensive medical condition and the leading cause of death, and hypertension being the most prevalent chronic condition, we should look to prioritize ways to prevent them. Luckily, one action can lower the risk of all of these chronic conditions and many others. A recent paper published in 2023 titled “Daily stair climbing, disease susceptibility, and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a prospective cohort study,” Song et al. found climbing more than five flights of stairs daily was associated with a lower risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) independent of disease susceptibility. Overall, it is safe to say that the question: stairs or elevator, has the potential to have more of an impact in our lives than we may originally think.

Song and colleague’s research was a prospective study using data from almost 500,000 (458,860 to be exact) adult participants in the United Kingdom. A prospective cohort means that the subjects are followed to observe future outcomes. Baseline data for stair climbing, sociodemographic (e.g., age, sex, ethnicity, education, average annual household income), and lifestyle (e.g., smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, and dietary pattern) factors were collected. Five years after baseline, this data was recollected with a median of 12.5 years of follow-up. Individuals were followed until the occurrence of the ASCVD incident, loss to follow-up, or death. The follow-up measured stair climbing and incidence of ASCVD, coronary artery disease, or ischemic stroke. ASCVD was considered to include coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, or acute complications. To account for the role of individual disease susceptibility, the following were analyzed: levels of genetic risk score, 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and self-reported family history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

What story did the data share? Among populations with varying susceptibilities, the cohort “demonstrated that climbing more than five flights of stairs daily was associated with over a 20% lower risk of ASCVD”. Participants who reported starting to stair climb at baseline but stopping stair climbing (meaning stair climbing less than 5 times a day) at the second examination had an observed higher risk of ASCVD. However, it is important to note that the behavior exhibited by these participants may actually be due to comorbidities or other risk factors that compelled them to reduce stair climbing. Therefore, interpretations of this data should factor in risk effect as a potential factor in the reduction in physical activity. Nonetheless, the data indicates that those who stopped stair climbing midway through actually showed worse results than those who hadn’t started stair climbing. This may show that consistently performing these smaller acts daily is more important than overexerting yourself for one day a week.

There are certainly more ways to integrate more daily movement without the use of stairs. Researchers from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, recently published a paper titled, “New principles, the benefits, and practices for fostering a physically active lifestyle” where they elucidated how ‘every minute counts’ for lifestyle movements and ‘going from nothing to something is the biggest bang for your buck’ in reference to Albert Bandura’s findings published in a 1977 paper on “Self-Efficacy”. This is important to remember as the biggest threshold isn’t going from 5 minutes of exercise to 30 minutes, but rather 0 minutes to 5 minutes. An effective way to confront these challenges is to think of SMART (Specific, Measureable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound) goals. SMART goals are related to the concept of self-efficacy (REF) which states that “individuals are more likely to pursue goals if they think they can accomplish them.” Since goals that are viewed as easily attainable are more likely to be accomplished, SMART goals can help guide one to create these ideal goals that will get the ball rolling. The moment you decide to increase physical activity in your life, think SMART. A SMART goal you can have for introducing stair climbing into your life would be, “I will climb at least 2 flights of stairs a day for 1 month to improve my cardiovascular health”. You can even practice this by creating a SMART goal for when you want to start implementing the exercise practices stated in this article!

Whether you decide to start today or in a couple weeks, with or without stairs, it is important to remember the research goals to emphasize the simplicity of the activity and time efficient nature of stair climbing detours. People at all stages of life benefit from less sedentary lifestyles, but implementing healthy habits early on further increases the benefits of non sedentary lifestyle practices. Some similar practical ways to increase the amount of steps taken in your life include activities from simply parking further away from your destination to even dancing whenever you hear music you enjoy. As a college student, I like to walk the longer scenic route between classes or even do smaller things like walk to the next bus stop instead of catching the one I am closest to. The first step (pun intended), no matter how small, can pave the way to a healthier, more active life. So, when you first encounter the decision of choosing the escalator or stairs, consider it not just a choice in the moment but as an investment in your long term well being.

How Exercise Improves Microbiome Health (and Vice Versa)

/in Gut Health, Healthful Nutrition, Movement & Exercise /by Maya ShettyBy Mary Grace Descourouez, MS, NBC-HWC

The human gastrointestinal tract is home to trillions of microorganisms that create the gut microbiome. The gut is where the body digests and absorbs nutrients from our food and, therefore, where we get our energy to perform daily human functions. Microbiota are microorganisms in the gut microbiome that help the body harvest energy, fight pathogens, and regulate immunity. Having a high diversity of microbiota helps us to process food effectively, providing the substrates and nutrients needed to keep us going throughout the day. Therefore, it is crucial to make lifestyle choices that promote a healthy and diverse microbiome.

Many people know that a nutrient-rich diet contributes to a healthy microbiome, however, research shows that movement and exercise may also have a positive effect, and, inversely, a healthy microbiome may improve athletic performance.

“It is a relatively new field, but available studies suggest a bidirectional relationship between performance and the health of the microbiome,” says Anne Friedlander, PhD, Exercise Physiologist and Assistant Director of Stanford Lifestyle Medicine. “People who are more active have a healthier and more diverse microbiome, and that, in turn, provides the person with the nutrients required to enhance physical and cognitive performance. It is a mutually beneficial relationship.”

How Exercise Improves the Microbiome

Movement and exercise have many benefits on our overall health, including positive effects on the microbiome. Studies show that athletes have a more diverse microbiome composition than non-athletes. Microbiome diversity is important because it helps make our food’s nutrients more bioavailable for optimal functioning of the body.

Another study found that active women were associated with high microbiome diversity compared to sedentary women. Specifically, researchers found that consistent physical activity increased the amount of 11 genera of “good” bacteria, including Bifidobacterium spp, Roseburia hominis, Akkermansia muciniphila, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii.

How the Microbiome Improves Athletic Performance

Just as exercise positively impacts the microbiome, emerging research shows that microbiome health may also play a part in enhancing exercise performance.

For example, a 2019 study showed that a specific gut microbiota in marathon runners may have enhanced their athletic performance on race day. In this study, researchers collected fecal samples from the runners before and after the marathon and compared them to microbiota of non-runners. The “good” bacteria Veillonella emerged as the most common in the runners, especially post marathon. Veillonella is a bacterial strain that converts exercise-induced lactate into propionate, which is a natural enzymatic process known to enhance athletic performance.

Researchers then put the Veillonella bacteria from the marathon runners into lab mice who underwent a treadmill exertion test to investigate the hypothesis that this bacterial strain enhances athletic performance. The results showed the mice improved performance by 13 percent after inoculation. This study is one of the first to infer that a healthy microbiome could enhance athletic performance.

“We have a long way to go to fully understand the complex system that involves the microbiome and athletic performance, but the early data look promising regarding gut health and exercise,” says Dr. Friedlander. “Exercise, along with eating fermented foods and fiber, is a great place to start if you want to improve your gut health and overall health.”

Resources

Pillars

Newsletter

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive emails from Stanford Lifestyle Medicine.