Data Spotlight on: Black Americans

While most Americans have seen improvements in sleep over the past decade, Black Americans continue to sleep significantly less than other groups. This trend has been examined both by researchers and the popular press.21,22 Researchers have found that Black Americans, in addition to getting shorter sleep, are also more likely to get poor quality sleep – spending less time in the most restorative stages of sleep23,24 – and to develop obstructive sleep apnea.25 Black Americans are also disproportionately affected by diseases that have been associated with poor sleep, such as obesity, diabetes,26 and cardiovascular disease.25

The exact reason(s) for Black Americans’ poor sleep is still unclear, though researchers have proposed potential contributing factors, largely related to the social inequality Black Americans face in the U.S.:

Experiences of discrimination: the stress of racial discrimination has been associated with spending lesstime in deep sleep and more time in light sleep among Black Americans.24

Living environment: neighborhood quality has been linked to sleep quality,27 and Stanford researchersfound that racial and income disparities persist in neighborhoods.28 They found that while middle-income white families are more likely to live in resource-rich neighborhoods with other middle-income families, middle-income black families tend to live in markedly lower-income, resource-poorneighborhoods.

Work and income inequality: for example, shift work can cause irregular working hours. This leadspeople to suffer “social jetlag,”; a discrepancy in sleep hours between work and free days,29 leading tosymptoms of sleep deprivation.

Lack of access to resources: particularly sleep-related healthcare and education.

Some of these factors are being addressed directly. Professor Girardin Jean-Louis from New York University and his team have devoted themselves to addressing the access to healthcare and education issue among local black communities in New York by tailoring online materials about obstructive sleep apnea to the culture, language, and barriers of specific communities.30 Professor Jamie Zeitzer and his team at Stanford recently completed an initial clinical trial of a drug (suvorexant), which was found to help people who work at night get three more hours of sleep during the day.31 Professor Zeitzer’s ultrashort light flash therapy (discussed above) may also help with shift work. These interventions could help to improve sleep for Black Americans, but they may not make up the whole picture; it could be that the underlying social inequality needs to be addressed in order to fully close the sleep gap.

Thanks to Jamie Zeitzer and Ken Smith for their insights and edits on this report.

References

- Deak, M., & Epstein, L. J. (2009). The history of polysomnography. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 4(3), 313–321.

- Cheung, J., Zeitzer, J. M., Lu, H., & Mignot, E. (2018). Validation of minute-to-minute scoring for sleep and wake periods in a consumer wearable device compared to an actigraphy device. Sleep Science and Practice, 2(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-018-0029-8

- Gao, C., Terlizzese, T., & Scullin, M. K. (2019). Short sleep and late bedtimes are detrimental to educational learning and knowledge transfer: An investigation of individual differences in susceptibility. Chronobiology International, 36(3), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2018.1539401

- O’Brien, E. M., & Mindell, J. A. (2005). Sleep and risk-taking behavior in adolescents. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 3(3), 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15402010bsm0303_1

- Rusnac, N., Spitzenstetter, F., & Tassi, P. (2019). Chronic sleep loss and risk-taking behavior: Does the origin of sleep loss matter? Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 17(6), 729–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2018.1483368

- Bioulac, S., Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A., Arnaud, M., Sagaspe, P., Moore, N., Salvo, F., & Philip, P. (2017). Risk of motor vehicle accidents related to sleepiness at the wheel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep, 40(10). https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx134

- Franzen, P. L., & Buysse, D. J. (2008). Sleep disturbances and depression: Risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(4), 473–481.

- Tsuno, N., & Ritchie, K. (2005). Sleep and Depression. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 16.

- Lv, W., Finlayson, G., & Dando, R. (2018). Sleep, food cravings and taste. Appetite, 125, 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.02.013

- Pardi, D., Buman, M., Black, J., Lammers, G. J., & Zeitzer, J. M. (2017). Eating decisions based on alertness levels after a single night of sleep manipulation: A randomized clinical trial. Sleep, 40(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsw039

- Chennaoui, M., Arnal, P. J., Sauvet, F., & Léger, D. (2015). Sleep and exercise: A reciprocal issue? Sleep Medicine Reviews, 20, 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.008

- Cappuccio, F. P., Taggart, F. M., Kandala, N. B., Currie, A., Peile, E., Stranges, S., & Miller, M. A. (2008). Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep, 31(5), 619-626.

- Althoff, T., Horvitz, E., White, R. W., & Zeitzer, J. (2017, April). Harnessing the web for population-scale physiological sensing: A case study of sleep and performance. In Proceedings of the 26th international conference on World Wide Web(pp. 113-122).

- Roth, T. (2007). Insomnia: Definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 3(5 Suppl), S7–S10.

- Qaseem, A., Kansagara, D., Forciea, M. A., Cooke, M., & Denberg, T. D. (2016). Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165(2), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2175

- Jacobs, G. D., Pace-Schott, E. F., Stickgold, R., & Otto, M. W. (2004). Cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy for insomnia: A randomized controlled trial and direct comparison. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(17), 1888–1896. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.17.1888

- Manber, R., Bei, B., Simpson, N., Asarnow, L., Rangel, E., Sit, A., & Lyell, D. (2019). Cognitive behavioral therapy for prenatal insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 133(5), 911–919. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003216

- Ong, J. C., Crawford, M. R., Dawson, S. C., Fogg, L. F., Turner, A. D., Wyatt, J. K., Crisostomo, M. I., Chhangani, B. S., Kushida, C. A., Edinger, J. D., Abbott, S. M., Malkani, R. G., Attarian, H. P., & Zee, P. C. (2020). A randomized controlled trial of CBT-I and PAP for obstructive sleep apnea and comorbid insomnia: Main outcomes from the MATRICS study. Sleep. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsaa041

- Karlin, B. E., Trockel, M., Taylor, C. B., Gimeno, J., & Manber, R. (20130415). National dissemination of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in veterans: Therapist- and patient-level outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(5), 912. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032554

- Kaplan, K. A., Mashash, M., Williams, R., Batchelder, H., Starr-Glass, L., & Zeitzer, J. M. (2019). Effect of light flashes vs sham therapy during sleep with adjunct cognitive behavioral therapy on sleep quality among adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 2(9), e1911944. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11944

- Resnick, B. (2015, October 27). The Racial Inequality of Sleep. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/10/the-sleep-gap-and-racial-inequality/412405/

- Resnick, B., & Barton, G. (2018, April 12). Black Americans don’t sleep as well as white Americans. That’s a problem. Vox. https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2018/4/12/17224328/sleep-gap-black-white-minority-america-health-consequences

- Beatty, D. L., Hall, M. H., Kamarck, T. A., Buysse, D. J., Owens, J. F., Reis, S. E., Mezick, E. J., Strollo, P. J., & Matthews, K. A. (2011). Unfair treatment is associated with poor sleep in African American and Caucasian adults: Pittsburgh SleepSCORE project. Health Psychology, 30(3), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022976

- Tomfohr, L., Pung, M. A., Edwards, K. M., & Dimsdale, J. E. (2012). Racial differences in sleep architecture: The role of ethnic discrimination. Biological Psychology, 89(1), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.09.002

- Olafiranye, O., Akinboboye, O., Mitchell, J., Ogedegbe, G., & Jean-Louis, G. (2013). Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease in blacks: A call to action from association of black cardiologists. American Heart Journal, 165(4), 468–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2012.12.018

- Jackson, C. L., Redline, S., Kawachi, I., & Hu, F. B. (2013). Association between sleep duration and diabetes in black and white adults. Diabetes Care, 36(11), 3557–3565. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-0777

- Hale, L., Hill, T. D., & Burdette, A. M. (2010). Does sleep quality mediate the association between neighborhood disorder and self-rated physical health? Preventive Medicine, 51(3–4), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.017

- Reardon, S. F., Fox, L., & Townsend, J. (2015). Neighborhood income composition by household race and income, 1990–2009. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 660(1), 78–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716215576104

- Wittmann, M., Dinich, J., Merrow, M., & Roenneberg, T. (2006). Social jetlag: Misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiology International, 23(1–2), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420520500545979

- Jean-Louis, G., Robbins, R., Williams, N. J., Allegrante, J. P., Rapoport, D. M., Cohall, A., & Ogedegbe, G. (2020). Tailored Approach to Sleep Health Education (TASHE): A randomized controlled trial of a web-based application. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8510

- Zeitzer, J. M., Joyce, D. S., McBean, A., Quevedo, Y. L., Hernandez, B., & Holty, J.-E. (2020). Effect of suvorexant vs placebo on total daytime sleep hours in shift workers: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), e206614. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6614

Scientists have devoted themselves to the study of sleep for over 70 years, but explanations about how and why we sleep remain elusive. What we have learned is that sleep is critical to brain function; in order for the brain to perform at its best, the average adult today needs 7-9 hours per night, every night. We know that the circadian rhythm, a near-24-hour “clock” inside the body that helps to anticipate when sleep should occur, uses environmental stimuli, especially light exposure, to synchronize itself to the outside world. Scientists typically break the sleep cycle into five stages, the most well-known of which are deep sleep and rapid eye movement (REM), which was discovered by the late Stanford Professor William Dement in the late 1950’s.

Scientists have devoted themselves to the study of sleep for over 70 years, but explanations about how and why we sleep remain elusive. What we have learned is that sleep is critical to brain function; in order for the brain to perform at its best, the average adult today needs 7-9 hours per night, every night. We know that the circadian rhythm, a near-24-hour “clock” inside the body that helps to anticipate when sleep should occur, uses environmental stimuli, especially light exposure, to synchronize itself to the outside world. Scientists typically break the sleep cycle into five stages, the most well-known of which are deep sleep and rapid eye movement (REM), which was discovered by the late Stanford Professor William Dement in the late 1950’s.

Stanford Lifestyle Medicine, led by Stanford Center on Longevity faculty affiliates Dr. Michael Fredericson and Dr. Douglas Noordsy, has compiled a list of best practice recommendations for individual behavior, such as adhering to a consistent sleep schedule and incorporating exercise, which can be viewed on page two of this report’s data update, and on the Lifestyle Medicine

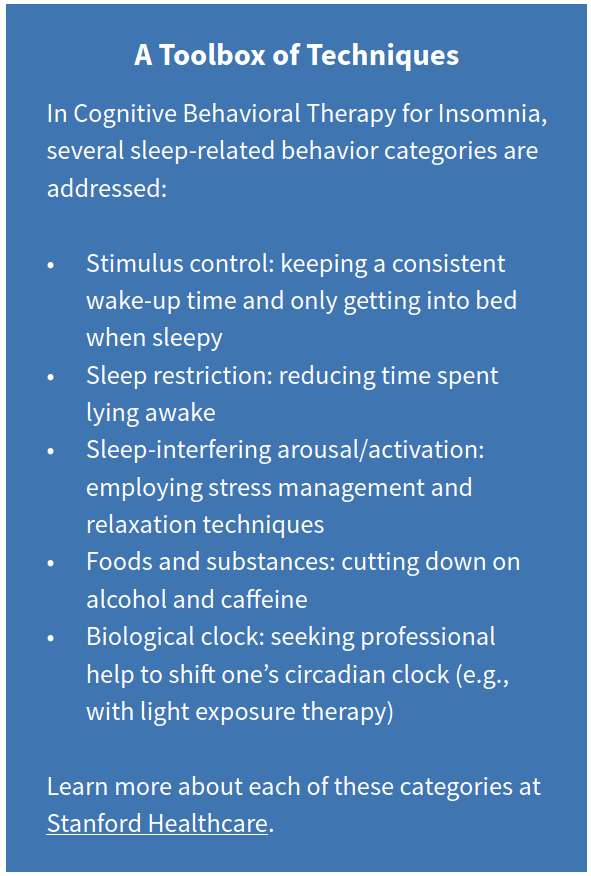

Stanford Lifestyle Medicine, led by Stanford Center on Longevity faculty affiliates Dr. Michael Fredericson and Dr. Douglas Noordsy, has compiled a list of best practice recommendations for individual behavior, such as adhering to a consistent sleep schedule and incorporating exercise, which can be viewed on page two of this report’s data update, and on the Lifestyle Medicine  Approximately 1/3 of adults report at least one symptom of insomnia,14 which is characterized by difficulty falling and/or staying asleep. Sometimes this is due to a life event (acute insomnia), an underlying health issue, or it may be chronic, otherwise unexplained sleeplessness. The American College of Physicians recommends that adults try cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI) as their first approach to treating primary insomnia.15 For people willing to do such therapy, CBTI has been found to be as or more effective than drug therapy for chronic insomnia.16 CBTI has also been found to alleviate symptoms of insomnia during pregnancy17 and in people with comorbidities such as obstructive sleep apnea.18

Approximately 1/3 of adults report at least one symptom of insomnia,14 which is characterized by difficulty falling and/or staying asleep. Sometimes this is due to a life event (acute insomnia), an underlying health issue, or it may be chronic, otherwise unexplained sleeplessness. The American College of Physicians recommends that adults try cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI) as their first approach to treating primary insomnia.15 For people willing to do such therapy, CBTI has been found to be as or more effective than drug therapy for chronic insomnia.16 CBTI has also been found to alleviate symptoms of insomnia during pregnancy17 and in people with comorbidities such as obstructive sleep apnea.18 CBTI is a

CBTI is a