Executive Summary

In April of 2016, the Stanford Center on Longevity hosted a workshop sponsored by CDW titled “Wearable Devices & the 24-hour Activity Cycle: A Framework for Developing Daily Activity Recommendations” that brought together top researchers and leaders from academia and industry to examine a new hypothesis; namely that health recommendations would be more effective if they could include all health-related activity domains (exercise, sleep, sedentary behavior, and light activity) experienced in a daily cycle. This is a shift in paradigm from traditional recommendations, which have been created separately by individual medical research fields.

Two days of presentations, discussions, and working sessions led the researchers to outline a new model for activity research – the 24 Hour Activity Cycle (24HAC). Leveraging the capabilities of high-quality consumer wearables and research devices, it is possible to create comprehensive recommendations for how people should structure physical activity and sleep that are aligned with how they actually spend their day and that incorporate how one activity affects another (e.g. – how exercise affects sleep). The 24HAC also opens up the possibility of tailoring recommendations to the individual based on wearable device feedback. This is especially important for older individuals, who often get the bulk of their activity through lower intensity activities such as walking, gardening, shopping, and housework and who may be concerned that they are not meeting existing activity guidelines.

This white paper outlines the conclusions and implications from the 24HAC workshop. For more detailed information, visit the workshop website at https://longevity.stanford.edu/wearable-devices//.

Lifestyle as Disease Prevention and Management

In 2015, researchers at the Stanford Center on Longevity submitted a paperi to the White House Conference on Aging highlighting the remarkable longevity advancements achieved by developed nations in the past 100 years:

“The first half of the 20th century witnessed gains in life expectancy largely due to reductions in infant and maternal mortality. Success was astounding. In a single century infant mortality decreased by 90 percent and maternal mortality decreased by 99 percent. In the second half of the century, life expectancy continued to increase due to medical advances, largely in the treatment of cardiovascular disease, which extended life expectancy in adulthood. All told, nearly thirty years were added to average life expectancy in a single century. Increases continue today, with three months added to life expectancy at 65 every year.”

The researchers also called for a national shift in priorities. With the great majority of the population now having the opportunity to live into old age, chronic conditions such as heart disease, cancer, and diabetes have replaced acute diseases like influenza as top causes of death. These chronic diseases are highly influenced by lifestyle choices and future health and longevity gains will likely be made through behavior modifications that help people increase physical activity, eat better, socialize more, and sleep soundly. One way of viewing this shift is working to keep people healthy longer, rather than waiting until they are sick to intervene.

Fortunately, advances in science and technology are well-positioned to make inroads into lifestyle management. This is particularly true for physical activity, which is recognized almost universally as leading to a wide array of positive health outcomes. A strong research base is already in place on how exercise, sleep and more recently sedentary behavior influence our health. Wearable devices have exploded onto the scene; growing in capability and becoming mainstream in terms of cost and availability. Virtually universal connectivity, cloud computing, and advances in big data analytics bring the promise of truly personalized recommendations on the best ways to optimize our health. Our current activity guidelines, however, are rooted in past measurement capabilities. It is time to take a more multi-disciplinary and comprehensive approach to activity that takes advantage of all the tools at hand.

The 24 Hour Activity Cycle – A New Approach

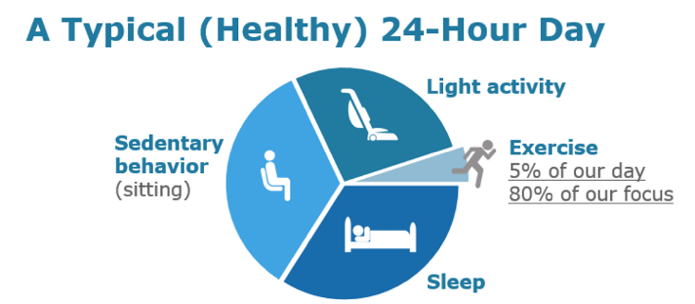

The 24 Hour Human Activity Cycle (24 HAC) takes a more holistic approach to how we view physical behavior. Rather than focusing on a single domain of activity (such as exercise), this approach focuses on the total make-up a 24-hour day. The cycle can be visualized as a 24 hour “clock”, with activities broken into four domains: sleep, exercise, sedentary behavior, and light activity.

There are several advantages to viewing activity in this way:

Unlike current guidelines, this approach takes into account ALL of the day’s activities. Currently, an individual could be considered as meeting the guidelines for healthy activity if she were to do almostnothing all day, as long as she spent a half hour at the gym. Conversely, a hotel maid could spend all day on her feet, pushing vacuums and making beds, and go to bed exhausted, but concerned that she “didn’t exercise”. Emerging physical activity research is finding that even low levels of activity contribute to better health. This is particularly important for older individuals, for whom traditional “exercise” may not be attainable.

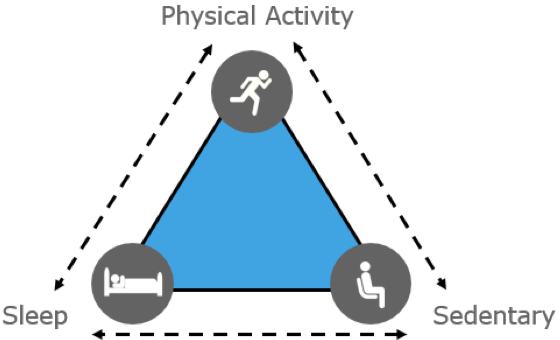

Unlike current guidelines, this approach takes into account ALL of the day’s activities. Currently, an individual could be considered as meeting the guidelines for healthy activity if she were to do almostnothing all day, as long as she spent a half hour at the gym. Conversely, a hotel maid could spend all day on her feet, pushing vacuums and making beds, and go to bed exhausted, but concerned that she “didn’t exercise”. Emerging physical activity research is finding that even low levels of activity contribute to better health. This is particularly important for older individuals, for whom traditional “exercise” may not be attainable.- The approach better reflects the reality that as time spent in one activity is increased, the time spent in another must decrease (as there are only 24 hours in a day). Changes in behavior are more accurately reflected as “trades” based on how people choose to spend their time.

- The 24 HAC allows individuals to better recognize the interactions between activity domains. Research shows that exercise promotes better sleep, which in turn tends to lead to better alertness and more activity. After a hard workout, an individual may NEED some sedentary behavior for recovery, and the 24 model recognizes this interaction.

Although the 24 HAC approach is new, it is built on the foundation of decades of research into the four individual activity categories:

1. Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity

Exercise science is probably the best understood of the domains. The field is often dated back to a study published in 1947 by Jeremy Morris, a Scottish epidemiologistii. He noted that London bus conductors were in generally fitter and healthier than drivers and hypothesized that this was because conductors were on their feet all day while the drivers sat (somewhat amusingly including trouser size as an outcome variable). Since then, thousands of studies have confirmed the relationship between physical activity and health and have linked exercise to improvements in a wide range of conditions including heart disease, cancer, obesity, and diabetes. In recent years this research has expanded to include strong correlations with brain health, including reduction in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, as well as improvements to mood disorders like depression. The most recent guidelines for exerciseiii come from the American Heart Association and the American College of Sports Medicine in 2008, and recommend that individuals get at least 150 minutes of moderate exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous exercise per week.

2. Sleep

The importance of sleep has been recognized even longer than exercise, although its mechanisms are less understood. Ancient Egyptian scrolls have been found recommending poppy seeds as a remedy for insomnia – the first opioid prescriptions. Modern scientific study, however, is generally recognized as beginning with the opening of the Stanford Sleep Clinic by Dr. William Dement in 1970. Even with almost 50 years of study, the basic reasons for sleep remain a mystery. What has been established beyond a shadow of a doubt is that a lack of sleep can have terrible consequences. Heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, and a host of other chronic conditions can result from too little sleep. The Harvard Medical School reports that even a single night of poor sleep for someone with hypertension leads to elevated blood pressure the entire following dayiv. In 2015, the American Sleep Association published a set of age-dependent guidelines that recommend seven or more hours of sleep for adults. Recognizing that too much sleep can be detrimental, the guidelines for those 61-64 years of age are listed as 7-9 hours, with 7-8 hours recommended for those over 65.

3. Sedentary Behavior

Recognition of sedentary behavior (mostly sitting) as a health risk separate from lack of exercise is a relatively new science. Epidemiologist Neville Owen at the University of Queensland is often recognized as the first to begin serious study of sitting as a health risk. In 2008, he and a group of authors from Australia and the Pennington Research Center in Louisiana published a seminal paper outlining a new metabolic hypothesis for sitting as a risk factor for obesity, diabetes, and heart disease and calling for the development of national health recommendations for sittingv. As of now, these guidelines remain undefined, although the popular press has been rife with headlines like “sitting is the new cancer”. What has been established is that individuals who sit for long periods of time are more likely to incur chronic disease and die sooner than those with limited sitting time. For now, recommendations are to minimize the time spent in prolonged sitting and to take breaks as often as possible. Development of scientifically validated guidelines in this area is the biggest hurdle to establishing 24 HAC guidelines.

4. Light Activity

The “light activity” domain is relatively undefined and usually considered as “other”: movements not described by exercise, sleep, or sedentary behavior. While there is little science categorizing and evaluating these activities, they constitute the bulk of active time in a typical the day. This is especially true for seniors, who may not be able to adhere to traditional exercise guidelines. Tasks such as housework, shopping, cooking, and gardening are all valuable ways in which we stay active. And there is increasing scientific data suggesting that these lower levels of activity are important to our health.

The Role of Wearables

Reasonably priced consumer wearable devices that can accurately measure activity hold the promise of “unlocking” the 24 HAC as a useful tool for helping individuals structure their day to promote better wellness. This is especially true for devices that can both measure movement through the use of accelerometers and monitor heart rate as a way of gauging the intensity of activities at a personal level. A recent study attempting to record individuals’ time spent in exercise, sleep, and sedentary behavior using self-reported time illustrated why objective measurement so critical. In the study, each individual was asked to estimate the time spent in each domain. When added together, the total significantly exceeded 24 hours per day. Given this tendency to misreport how we spend our time, it becomes clear that it is nearly impossible to develop accurate interventions without objective data.

New wearables are being developed rapidly. The website vandrico.com/wearables works to catalogue this development and currently lists over 420 available devices. A number of these can already measure physical activity, sleep, and even provide useable indicators of sedentary behavior. More devices with these capabilities are in development and companies are looking to add measurement of biomarkers such as glucose level, blood pressure, and lactose that “report” on the status of the body as well as including additional sensors that can measure things like light, sound, and location in ways that provide more context for the activity. The integration of these wearables with previously established health recommendations is a challenge, however, as technology development and medical research often do not intersect.

The highly competitive and proprietary nature of the wearables business has slowed progress in developing validated 24 HAC data. Most consumer devices only output activity readings after applying proprietary algorithms, resulting in appealing user interfaces, but making it difficult for researchers to evaluate the quality of measurements or to compare data from different devices. Research devices have better validation and transparency into the signal processing algorithms, but are often expensive and more cumbersome for the user. At the time of this writing, there is no accepted “standard” device that researchers can use to conduct studies and compare results. The creation of 24HAC recommendations is stalled largely because of these challenges.

The 24 HAC Now and Promise for the Future

Even with current issues, it is possible to start developing 24 HAC cycle-based interventions. Wearables have reached a stage where they can reliably create 24 hour “clocks” for individuals. Though it is difficult to measure objective data quality, readings from a single device for a single individual can be used to spot trends and measure adherence to recommendations. For example, an individual could wear a device for a month-long “baseline” period and establish a pattern of activity. These patterns could be monitored on a week-to-week basis and trends could indicate potential problems or areas for improvement. A normally active person becoming sedentary could alert a caretaker to investigate possible changes in health or socialization status. More proactively, a doctor or trainer could look at wearable data and make general recommendations such as “you are not sleeping well – add a 20 minute walk to your day” and check back to see if the person has improved behavior. Another potential benefit of the 24 HAC involves prescription medication. Knowing how activity and sleep patterns change as a result of new medications and dosage changes provides valuable and most importantly objective feedback on side effects such as drowsiness, lethargy, and dizziness (which may lead individuals to be more sedentary).

If the issue of data sharing and validity could be overcome, very large data sets could be created and machine learning algorithms applied to identify patterns in the data, linking them to health outcomes. This would begin a beneficial feedback loop in which interventions could be much more rapidly tested and evaluated. Of special value to older adults, these interventions could be tailored to individual health status and physical capability, meaning that we could advise individuals on the best level of activity for their particular situation.

While technology will likely never completely replace a human caretaker, these types of systems would also allow providers to leverage their caregiver resources better. With data in hand and advice from expert systems, caretakers could identify individuals who might need timely attention while simultaneously keeping tabs on a larger group of customers. Such feedback also serves as a guide to motivated seniors who do not understand how their activity patterns are affecting their quality of life.

National 24 Hour Activity Guidelines

Large amounts of high quality data could eventually lead to the development of true 24-hour activity guidelines at a population level. These guidelines would likely be very different than existing recommendations, which for the most part attempt to recommend activity levels in a vacuum for broad swaths of the population. New approaches might be more akin to “national algorithms”, which could incorporate data gathered from the individual on sleep, all levels of activity, biomarkers, demographic variables (such as age) and even variables such as amount of sunlight encountered to recommend patterns of behavior that correlate to positive health outcomes.

The path to such guidelines is likely to be incremental, starting with recommended ratios of the 24 HAC domains broken down by age and gender. As more data accumulates and is compared to health outcomes, approaches will become more sophisticated. When the guidelines become more specific, they are in turn likely to drive wearables to become more accurate for important activity domains, more affordable (as volume increases), and more user-friendly – always a plus for seniors using new technology.

Conclusion

Wearables are already having impact on how people stay active. Devices from companies such as Fitbit, Samsung, Garmin, and Apple are being used daily by thousands of people to measure their exercise. With the 24 Hour Activity Cycle, we can expand this to measure sleep, sedentary behavior, and light activity, and combine the data to create a more comprehensive picture of a person’s day. For seniors in particular, this means that wearables can now start to help them optimize their own personal activity profile to one that fits their specific capability and goals. In the long term, these devices hold the promise of leading the way to more personal and more effective national guidelines on activity. Guiding individuals to a personalized optimal daily activity cycle is the true long term objective of 24HAC research.

Citations

i Carstensen LL, Rosenberger ME, Smith K et al. “Optimizing Health in Aging Societies”. Public Policy Aging Rep 2015;25:38–42.

ii Morris JN, Kagan A, Pattison DC, et al. “Incidence and prediction of ischaemic heart-disease in London busmen.” Lancet 1966;2;553-559.

iii Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, Nieman DC, Swain DP; American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand: quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor tness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1334–1359.

iv MullingtonJM,HaackM,TothM,SerradorJ,Meier-EwertH.Cardiovascular,In ammatoryandMetabolicConsequencesofSleepDeprivation. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 2009;51(4):294-302. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2008.10.003.

v Hamilton MT, Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Zderic TW, Owen N. Too Little Exercise and Too Much Sitting: Inactivity Physiology and the Need for New Recommendations on Sedentary Behavior. Current cardiovascular risk reports. 2008;2(4):292-298. doi:10.1007/s12170-008-0054-8.