In September of 2019, on the shores of Lake Como, a small group of experts reflecting a range of countries and disciplines came together to discuss a global longevity agenda. The event was organised by the Stanford Center on Longevity and The Longevity Forum and was held at Bellagio, with generous support from The Rockefeller Foundation and Prudential Assurance Company Singapore.

We came together to identify core components of a productive longevity agenda, to explore the extent to which countries face similar issues, and to better understand the key issues and how governments and societies can address them. Ultimately, we aim to share best practices and help to cultivate thriving long-lived societies.

Why a Longevity Agenda?

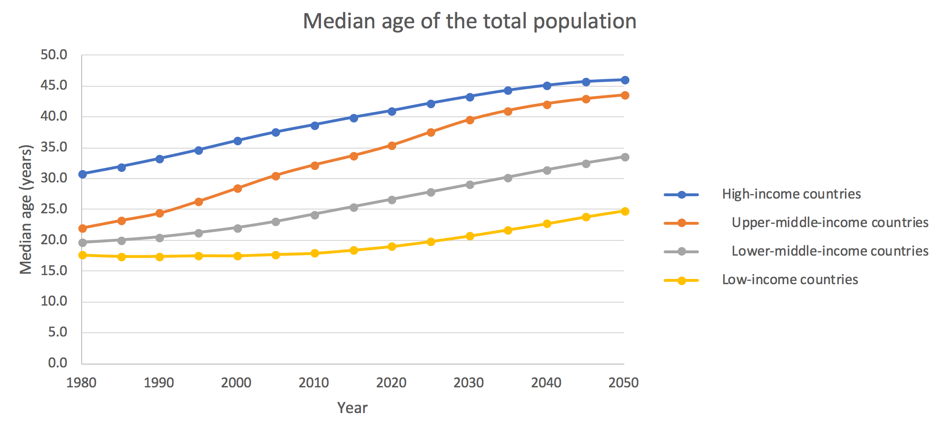

As a result of falling birth rates and longer lives societies are ageing. Falling birth rates mean that younger cohorts are smaller and more people living for longer makes older cohorts larger. The result is a change in the distribution of age in societies such that around the world the median ages of populations are increasing. The process is furthest advanced in the richest countries but as Figure 1 shows the process is underway globally – just from different starting points.

Goals

Resources

“A Longevity Agenda for Singapore”

“A Longevity Agenda for Singapore”

Hosted at a November launch meeting by Prudential Singapore, the global longevity principles and agenda discussed by the experts at the Bellagio meeting are introduced in the context of “A Longevity Agenda for Singapore.” Read

“A Global Agenda for a New Map of Life”

“A Global Agenda for a New Map of Life”

White Paper prepared for the Bellagio Global Longevity Agenda Meeting Read

Ageing is really about how we change with the passing of time (in mathematical terms it’s the derivative of life with respect to time!) and that is something that happens to all of us at every point in time, whatever our age. However, in general ageing has come to refer to the end of life with primary focus on supporting those who are old.

Ageing societies raise a number of challenging economic and social issues. They raise the prospect of lower economic growth as well as rising health and pension costs. When a growing proportion of the population are aged over 65 it also requires a dramatic shift in how health care is provided as well as challenges around who will care for an older population.

Rightly, a number of institutions, both intergovernmental as well as national, are focused on supporting this ageing society and providing support for positive ageing as the proportion of the world aged over 65 grows.

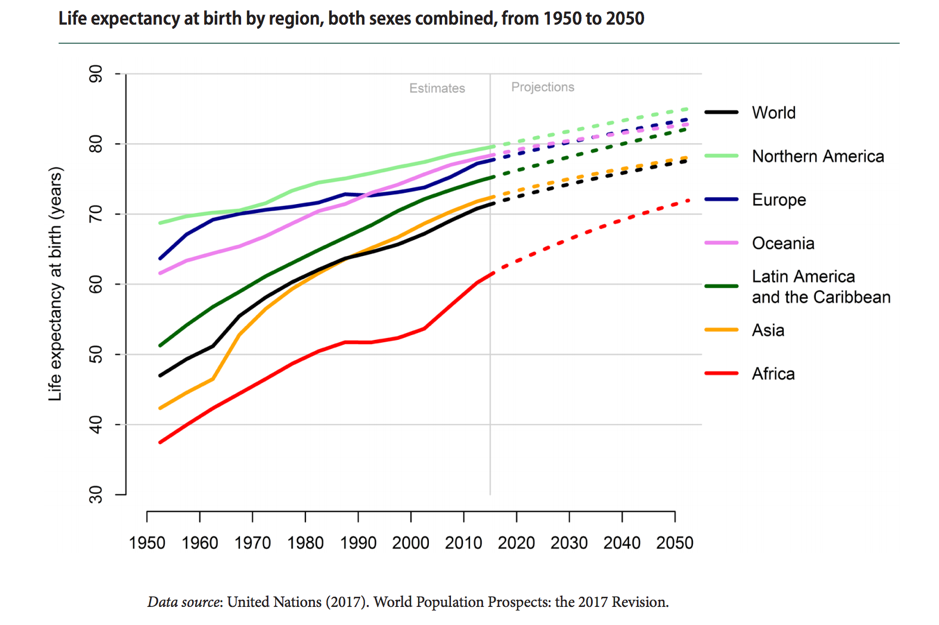

In contrast, a focus on longevity takes a different perspective to this ageing society narrative. It is based not on any one stage of life but instead on the ‘duration’ of lives. As Figure 2 shows, life has got longer and is likely to get longer still. The longevity agenda concerns how best to respond to longer lives.

If across the world life expectancy is increasing what does it mean in each society for people of all ages when they look forward and have more time ahead of them? How should family life, education, work, financial preparedness, and health practices change when people come to face century-long lives?

Further because this increase in the duration of life is happening to most people in all countries its changing society in major ways. In the richest nations as more people survive into their 70s and 80s cities, health systems, and pension programs must reckon with large numbers of older citizens. In many parts of Africa, where with declines in infant mortality many more individuals are surviving into their 20s and 30s, the potential of a demographic dividend lies ahead.

What does the longevity agenda involve?

Pretty much everything! It affects childhood and old age, education, relationships, works and careers. Finances and health. Crucially its about the whole of life and not just the end of life which is the focus of the ageing society approach. Across the world what is needed is a New Map of Life – the focus of a major research program at the Stanford Center on Longevity aimed at redrawing the map of life with new norms and guidance as to what we need at different stages and ages of life.

Pretty much everything! It affects childhood and old age, education, relationships, works and careers. Finances and health. Crucially its about the whole of life and not just the end of life which is the focus of the ageing society approach. Across the world what is needed is a New Map of Life – the focus of a major research program at the Stanford Center on Longevity aimed at redrawing the map of life with new norms and guidance as to what we need at different stages and ages of life.

Our old maps of life, the ones that we inherited from our parents or grandparents, are not well set up to deal with the increases in life expectancy that countries around the world are experiencing or the shifts that are occurring when so many live to later ages. Of course, new maps of life will vary from country to country and within countries as a function of social class and ethnic subcultures. They will also vary as a function of the stage of economic development and the point at which the demographic transition is situated in a given population.

The positive ageing agenda is part of these longevity concerns. We need to help support the growing number of older people and think differently about old age. The struggles with deeply entrenched ageist views are one of the most important and difficult aspects of creating a new map of life.

But the required changes work their way through the whole life course and aren’t just about the ‘old’. If there are more old people and more need of caring then within families and communities we need to look for ways to provide that caring at other stages of the life cycle. Then of course if we know we are likely to live for longer its important to take steps today to try and ensure that people age as healthily as possible and prepare themselves for the next stage of life.

The result is changes in all the major life decisions we make – when we form (or dissolve) relationships and with whom, when we gain our education and how we shape our careers or when we work and how we balance at each stage of life the various demands placed upon us.

As life lengthens across the world – whether its from 35 to 50 or 70 to 100 – individuals have more future and so they need to be more forward looking, more conscious of future options and investing in their future self, recognise that life is recursive so that what happens today affects your future and seize the opportunity that more time provides, making different trade offs between what you do with your time today relative to the future. Just as important, longer lives can afford us more time at all stages in life. Longer lives present opportunities to enjoy childhood, take breaks from work and education while weaving work and education across longer spans of life. Adolescence does not have to all-consumed with learning but can include volunteer and paid internships. Young adults can take sabbaticals. The middle-aged can return to school or develop avocations.

All of this requires a new map of life as every country adapts to these longer lives. The issues and context may vary as does life expectancy but the same need for social innovation around the life course is there.

What to look out for?

Given the variety of countries and disciplines it is hardly surprising that the week saw a broad range of debate and issues with much agreement as well as different areas of focus and perspective. A number of distinct themes did emerge around the longevity agenda.

Challenges and Opportunities

Changing social norms is hard, particularly when it comes to changing the structure of how we live our lives. In particular, a focus on chronological age is deep wired into many of our current practices and policies but as we live for longer, often in better health, old chronological milestones are increasingly less relevant.

However the longevity agenda is also about opportunities. With more time we can look to change and improve on current practices and find ways to better support our health, our relationships and support not just longer lives but better ones.

Not just about health

Health is at the heart of a good life and health systems play a crucial role in supporting longevity agendas. However much of our health is determined outside of the health system. Our sense of purpose and engagement, our social networks and whether we are lonely, our work and our education all play crucial roles in determining how healthy we are. Health systems are a key input into our health but maintaining health depends on a wide range of inputs.

Education over a lifetime

One of the key components of a longevity agenda needs to be a focus on making education something that can be supported over the life course. Historically education has been front loaded but as lives lengthen the need to deliver lifelong learning increases. Education needs to become like health, something that is worked on at all ages of life and where individuals have access to a system that can support and help them at any age.

Working longer

As people live longer they will need to work longer. Traditional views of saving enough money during working lives to support thirty or forty years of non-work are not feasible for individuals or governments. We can work differently, however, trading reducations in days and hours of the work week for more years of work. Opportunities to work part-time and full-time must be available throughout adulthood. We must reduce ageism in the world of work and find ways to optimize the age diversity of future workforces.

Focus on periods of vulnerability

If longevity is about the duration of life it is important to focus on critical periods where future prospects can be heavily shaped. Exactly when these are will vary from country to country and will also require considerable research focus to identify them.

In high income countries people entering their 50s are especially vulnerable to economic shocks and losing their job. This is an age where being reemployed is difficult but when many people hope to secure their finances for retirement. For lower income countries the availability of work for young adults is critical. In other countries it may be exposure to diseases in childhood . Depending on the context the longevity agenda needs to identify these key transition points and design support for those who are most disadvantaged.

Not on the agenda

Increasingly an ageing society is rising up the agenda of higher income countries. However that isn’t the case in most middle and low middle income countries because the current age of the population in these countries remains young. However that will change rapidly as these countries age in the decades ahead. That means the longevity agenda is especially important for them. What we do over the whole life course determines how we age. A longevity perspective is needed for countries who will age in the decades ahead. Initiatives such as the National Academy of Medicine’s Healthy Longevity Grand Global Challenge are particularly welcome initiatives from this perspective and shouldn’t be seen as just relevant to high income nations.

The point of being young is not simply to prepare for ageing well

Longer lives mean it is important to be more future orientated and take steps now to prepare for the future. However, as life extends it doesn’t mean that the present is entirely about preparing for the future. We mustn’t take an instrumentalist approach to childhood and early adulthood. We have to refashion the map of life but that means thinking about what is needed in isolation at each stage and not just about ensuring that we age well. Its true that the current young are the future old but longevity isn’t about establishing a life dominated by preparing for being old. Rather, we must begin to envision how best to use a gift of time at all stages in life.

An intergenerational focus

The increases in age diversity of populations often goes unnoticed. Yet this change is arguably even more transformative than ageing societies. Six (and more) age cohorts will be in the workforce at the same time. Four and five generations will be alive at the same time. In creating a new map of life it is important to ensure that changes are equitable from an intergenerational perspective. It isn’t about changing the life course to support any particular age group but creating a new map of life that supports human endeavours at all ages. In fact for many countries one of the great opportunities of a new map of life are to foster and nourish intergenerational connections that are mutually beneficial to old and young alike.

What is to be done?

After much debate and discussion over the week the notion that there was a distinct longevity agenda was clear. There is a need to find a new way of restaging the path of life. This is also a global challenge, albeit one that differs enormously from country to country. Demographic change is driving major behavioural change everywhere but clearly the life course issues in low income countries in Africa are strikingly different from those Asia.

Put any group of experts together for several days and inevitably a conclusion will be reached that more data are needed and more research required before firm recommendations can be made. When it comes to longevity this though seems eminently reasonable in order to identify key transition points and better understand what people in different countries are doing and what they would ideally like to do.

It was clear from the discussion though that are already a number of ideas that are being pursued and that could be replicated in different countries – governments introducing longevity councils, creating intergenerational committees to make community decisions and requiring generational audits so that policies don’t disadvantage one generation compared to another, shifting focus from period to cohort measures of life expectancy so more individuals are aware of life expectancy trends or supporting midlife audits to help people support longer working careers.

What next?

The meeting was convened as a first step in thinking about global longevity issues. The agenda is broad and one that will be shaped in the years ahead. A closing session discussed what needs to be done next, different routes that could help take the agenda forward and different institutions to approach to help us do so. In the next few months we will be deciding what to do next so watch out for further announcements. If you are interested in finding out more or in helping us with this agenda then please let us know by writing to [email protected].

1United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2019). World Population Prospects 2019. Retrieved from https://population.un.org/wpp/DataQuery/.

2United Nations (2017). World Population Prospects: the 2017 Revision.