Hsiao-Wen Liao, Tamara Sims

Overview

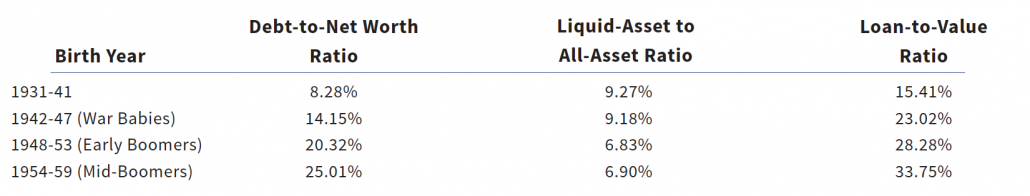

Many people consider financial knowledge to be essential to achieving financial well-being throughout their entire life. Yet, compared to men, women show consistently lower levels of both financial knowledge and financial literacy. Women are similarly at a disadvantage when it comes to achieving financial security. For instance, when examining the cumulative wealth of Americans age 50 years and older [1], older men were shown to have accumulated more wealth than women of the same age by $100,000 or more. Analysis done in the Health and Retirement Study also shows that older women earn significantly less than men of the same age in terms of both salary and pensions (Figure 4.1).

Many people consider financial knowledge to be essential to achieving financial well-being throughout their entire life. Yet, compared to men, women show consistently lower levels of both financial knowledge and financial literacy. Women are similarly at a disadvantage when it comes to achieving financial security. For instance, when examining the cumulative wealth of Americans age 50 years and older [1], older men were shown to have accumulated more wealth than women of the same age by $100,000 or more. Analysis done in the Health and Retirement Study also shows that older women earn significantly less than men of the same age in terms of both salary and pensions (Figure 4.1).

On average, older women earn lower salaries and pensions than men

Figure 4.1: Gender gaps in salary and pension incomes. Inflation adjusted to 2014 U.S. dollars.

The observed inequality in the second half of life is especially concerning because women are living longer than men [2] and will require more financial resources to support themselves independently. To adequately sustain future generations of women facing this situation, it’s going to be critical to address the issue of financial preparedness for women of all ages. Gender differences have often been cited as the reason for women’s lack of financial literacy, leading some experts to suggest that financial education would be an effective strategy for reducing the inequalities between men and women.

Yet mixed evidence of the success of such efforts suggests other barriers may be at play, such as a lack of confidence or involvement in financial decision making. A lack of clarity about the effects of these strategies and how these factors relate to one another has hindered practitioners from identifying when and for whom to intervene most effectively to optimize women’s financial futures.

Key Findings

- Regardless of age, women report being less confident than men both in terms of being unsure about answers on a financial literacy test and about their feelings regarding making key financial decisions, such as preparing taxes, taking out a home loan, and investing.

- Financial confidence predicts financial literacy for both men and women.

- Gender differences in the level of involvement in financial decisions depends on marital status.

- Among single people, men and women managed financial decisions to a similar degree across all age groups.

- Among married people, gender differences emerge across age groups:

- Married men are more involved in major financial decisions (e.g., investing).

- Married women are more involved in minor financial decisions (e.g., grocery budget).

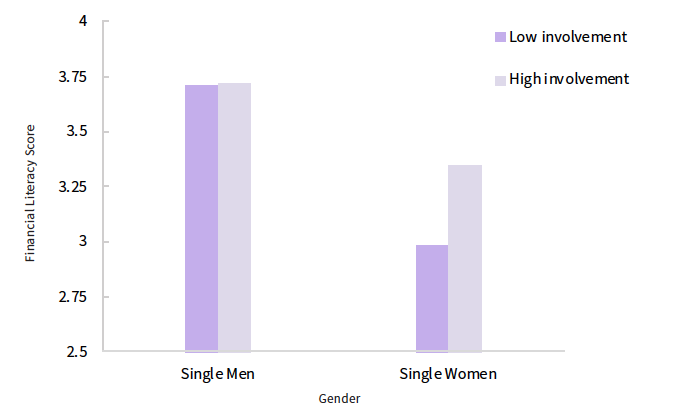

- Among single women, involvement in making financial decisions predicts higher financial literacy.

- Among single men, involvement in making financial decisions does not predict financial literacy, possibly because single men’s financial literacy scores and involvement in financial decisions are relatively high to begin with.

- Married people’s involvement in making financial decisions is unrelated to their financial literacy, so there is no connection for married women between how financially literate they are and how involved they are in making financial decisions.

- Women’s lower financial confidence not only explains lower financial literacy compared to men but also explains gender gaps in the age at which people start a long-term career.

According to a recent analysis of the National Capability Financial Survey [3], approximately 20 percent fewer married women than married men consider themselves to be the most financially knowledgeable person in their household across all generations. More younger women than older women claim to be the most knowledgeable, however, with a 7 percent uptick for married millennial women (53 percent) versus married boomer women (40 percent). One thing to note is that gender gaps in financial literacy among younger generations, such as for millennials, might be on the decline. For example, relative to men in previous generations:

- Younger women are more likely to be recruited for jobs and educational opportunities in math and thus may have attained higher levels of financial literacy. Research shows that girls perform as well as boys in standardized scores in math throughout high school [4]. Research also shows that more women are joining the workforce in some STEM fields, specifically physical and life sciences: The percentage of female workers in these fields rose from 36 percent in 2000 to 40 percent in 2009 and 43 percent in 2015 [5-6].

- Younger women are more likely to be college-educated than older women and thus may feel more confident in their ability to make financial decisions. In 2005, the number of women (32.3 percent) who had attained a four-year college degree was equivalent to the number of men who had done the same (32.7 percent) [7]. A recent report released by the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality indicates that more women than men are now attending college, offering more women the financial protection that a college degree offers [8].

- Younger women are more likely to be single longer and thus may be more likely to make their own financial decisions. The percentage of unmarried women between the ages of 25 and 29 increased from 26.9 percent in 1986 to 46.8 percent in 2009 [9]. One could extrapolate that younger women who marry later than their peers may be more confident in and feel more responsible for making major financial decisions than women from any previous generation.

Given the advancements described above, it’s reasonable to expect the gender gap in financial knowledge to be narrowing in younger generations. Nevertheless, multiple studies consistently show that men still outperform women in tests of financial literacy [10-12].

One reason for gender disparities in financial literacy may be due to women’s relative lack of confidence in making financial decisions [23]. Less well-known is how this relates to becoming involved in making different types of financial decisions (daily household duties vs. higher stakes, long-range planning, for instance). To investigate the potential intersecting roles of financial literacy, financial confidence, and financial decision-making involvement, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of Americans age 20 to 94 (N = 1734) through the RAND American Life Panel. Our goal was to better understand the importance of women’s financial literacy, financial confidence, and financial decision-making involvement relevant to achieving and maintaining financial security at all stages of adult life.

Financial literacy is a robust indicator of financial well-being, which has been linked to higher rates of financial security in later life [13]. Despite the changes in women’s life trajectories related to education and marriage, however, as well as the advocacy and implementation of financial education programs, the financial literacy gap among men and women still persists. In a 2018 report based on the National Financial Capability Study by FINRA, young millennial women showed lower financial literacy than both millennial men and all older male generations [3]. Notably, sociodemographic factors (e.g., age, race, education, income, marital status [11-12]) did little to explain gender disparities.

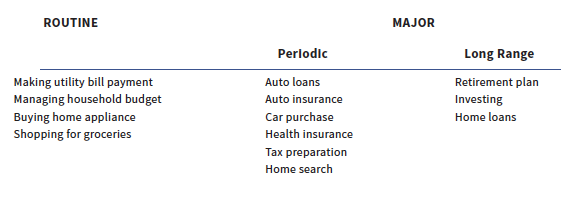

Using the same survey as in the study above, we assessed financial literacy with five multiple choice questions. (For the complete quiz, see endnote 19.) In our study, we targeted a sample stratified uniformly by gender, age group, and education status so that we could break down gender effects by each of these subgroups.

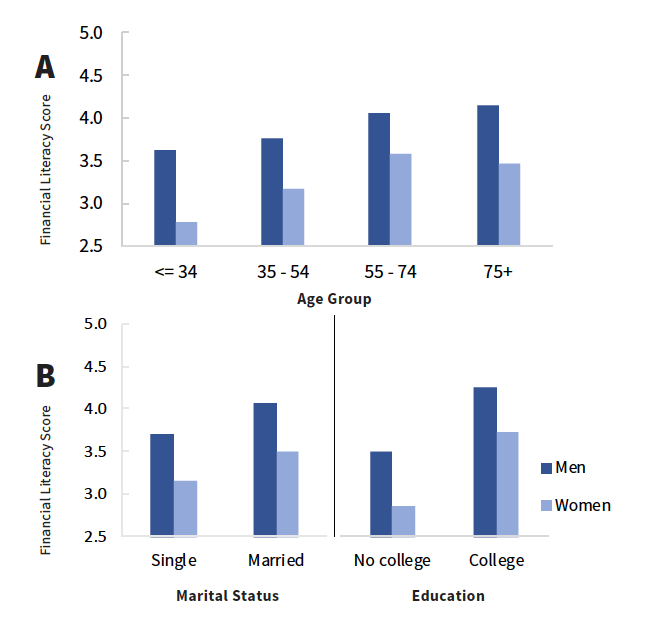

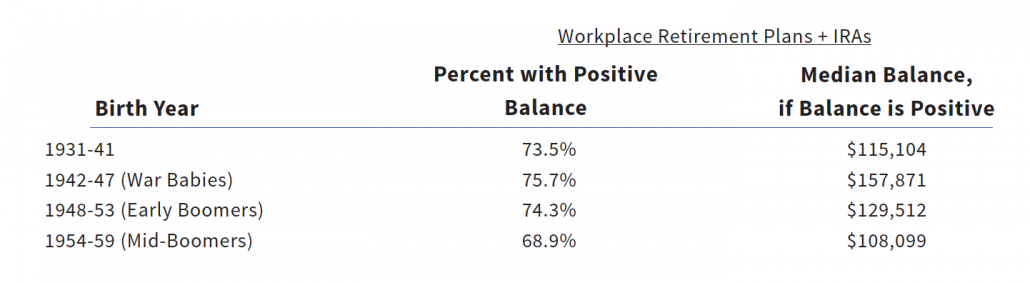

Consistent with other research, we found that age and gender affected financial literacy scores. Overall, the two younger groups scored lower on financial literacy than the two older groups. Additionally, women answered fewer questions correctly than men. Notably, millennial women (i.e., the youngest group ages < 35) scored the lowest on the financial literacy survey compared to both men and older women (Figure 4.2A).

Given generational shifts in the percentage of women graduating college and delaying marriage, we expected that gender differences in financial literacy would be less pronounced among younger, college-educated, and unmarried individuals. Yet women underperformed men across all age groups regardless of age, education, and marital status. We also found that, on average, married persons scored higher than single persons, and individuals with a bachelor’s degree scored higher than those without a bachelor’s degree. Statistically, gender gaps were robustly significant and didn’t differ between younger and older people, college-educated and non-college-educated people, and married and unmarried people (Figure 4.2B).

Women scored lower on a financial literacy quiz regardless of age group, marital status, and education level

Figure 4.2 Financial literacy scores by gender, according to age group (4.2A), marital status (4.2B left), and education

(4.2B right).

We found that gender disparities in finance are ubiquitous and persist irrespective of generational shifts in education and life trajectories. Yet how these gaps are produced and reinforced is still unclear. In the next analysis, we examined whether financial confidence and involvement in making financial decisions were pathways through which financial literacy could be changed. In contrast to previous research, we investigated financial confidence and involvement in financial decisions as determinants of financial literacy rather than as consequences of financial literacy.

Investigating Paths to Financial Literacy

Financial education is considered to be one of the most promising approaches to improving women’s financial security, but despite far-reaching educational efforts, gender gaps in financial literacy remain. It may be that the gender gap isn’t a reflection of lack of knowledge but rather of psychological beliefs and behavioral patterns that undermine women’s learning and performance on tests of financial knowledge. Drawing from research on gender and STEM education, we focused on financial self-efficacy, or confidence, and experience, or involvement in making financial decisions. A common assumption of financial education efforts is that increasing literacy will increase financial confidence and involvement in making financial decisions rather than the other way around. If financial confidence and involvement in making financial decisions are precursors to financial literacy, however, then addressing one or both of these factors first will be necessary for financial education programs to be effective.

Confidence in Making Financial Decisions

In daily life, women report lower confidence than men across many situations. Not only are gender differences in self-confidence ubiquitous, it tends to emerge early in life [15]. Our first goal was to examine whether a lack of confidence in financial decision making across adult life stages explains gender differences in financial literacy.

It has long been documented that women have lower self-esteem, generally speaking, than men [14]. Girls start to show a greater lack of confidence than boys in their ability to excel at tasks that require “being smart” as young as age six [15]. Women also repeatedly report feeling less capable at mastering mathematics [16], a skill that’s likely essential to acquiring financial literacy. More directly, American college-educated women report lower confidence in their ability to achieve financial goals compared to their male counterparts [17]. Women’s confidence has also been shown to explain a difference in financial behavioral outcomes, such as investing [17, 18]. Thus, confidence appears to be strongly tied to financial literacy, though a causal relationship between the two has been difficult to establish.

Involvement in Financial Decision Making

Research also points to the importance of “learning by doing,” which may explain gender gaps in financial literacy because women are less likely to practice making financial decisions, such as those involving wealth management [19]. To compound the issue, men are more likely than women to be responsible for financial decisions requiring higher levels of financial literacy as it is traditionally assessed [11]. For instance, in one study, about half of all men considered themselves to be the primary person responsible for filing taxes, tracking investments, and buying insurance versus about one-third of women. On the other hand, more women than men consider themselves to be the primary person in charge of daily household financial decisions, such as paying bills (women: 51.2 percent; men: 36.9 percent) and making short-term spending decisions (women: 43.2 percent; men: 24.6 percent). Notably, these types of decisions typically don’t require having the type of knowledge assessed in standard financial literacy tests.

Involvement in making major financial decisions has also been found to be associated with higher financial literacy among married couples, although this association is primarily driven by married men [11]. That is, married men who were highly involved in making various types of financial decisions, such as paying bills, preparing taxes, making spending plans, and tracking investments, scored higher on financial literacy tests than did uninvolved married men. Among married women, however, as involvement in making financial decisions increased, increases in financial literacy were minimal and only found among people making two types of decisions: preparing taxes and making long-term spending plans. It may be that married women, in particular, aren’t attributing their experiences in financial decision making to an inherent or learned knowledge of financial matters. Regardless, based on these findings, we also explored how marital status and gender interact to shape the associations between financial literacy, financial confidence and involvement in financial decision making.

In the current report, we examined whether gender differences in financial decision making emerge sequentially, beginning with gender differences in financial confidence and/or involvement in making financial decisions and subsequently leading to gender differences in financial literacy test scores. To do so, we tested a set of hypotheses to investigate the relationships among gender, financial decision making, and financial literacy as outlined below.

Path A: Confidence in Financial Decision Making

1. Women will be less confident than men in making financial decisions.

2. Distinct from involvement in major financial decisions, financial confidence will predict higher financial literacy and account for gender differences.

Path B: Involvement in Financial Decision Making

3. Women will be less involved than men in making major financial decisions.

4. Distinct from financial confidence, involvement in major financial decisions will predict higher financial literacy and account for gender differences.

A Closer Look

Financial Confidence, Involvement in Financial Decisions, and Financial Literacy Assessments

We measured financial confidence both in terms of the number of times a respondent indicated “Don’t know” on a quiz assessing financial literacy as well as in their self-reports of confidence in making various financial decisions [20, 22].

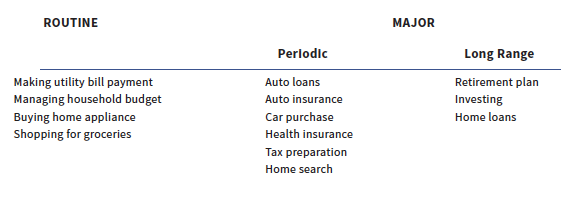

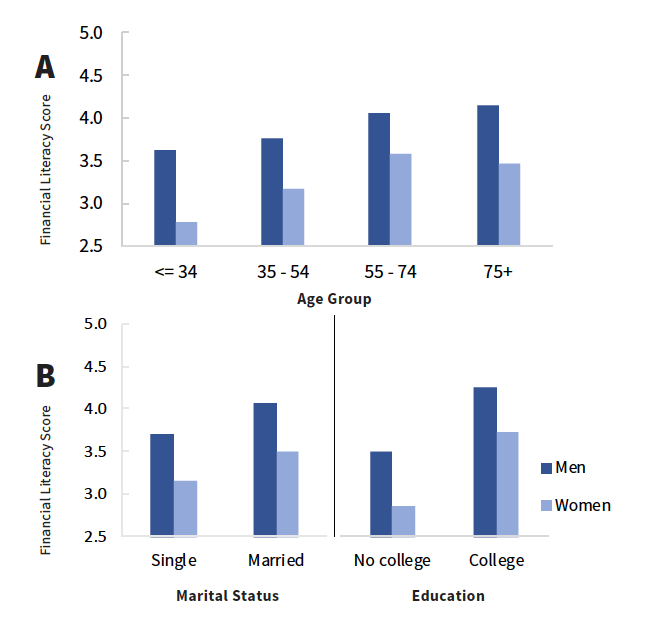

We assessed both confidence and involvement in financial decisions across what we termed “Routine” and “Major” decisions (Table 4.1). In addition to count of the traditional “Don’t know” answers described above, we also explicitly asked respondents to indicate how confident they felt when making each of these decisions using a five-point scale (1 = not at all confident; 5 = extremely confident). Additionally, we asked respondents to indicate on a five-point scale how involved they were in each of the decisions shown below, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of involvement (1 = I am the sole decision maker; 3 = I make these decisions with someone else; 5 = Someone else is the sole decision maker).

Table 4.1 Routine and Major Financial Decisions

Note. Periodic and long-range major financial decisions were grouped together as non-household decisions in our analyses because they showed similar patterns of gender differences.

Path A: Confidence in Financial Decision Making

1. Women will be less confident than men in making financial decisions.

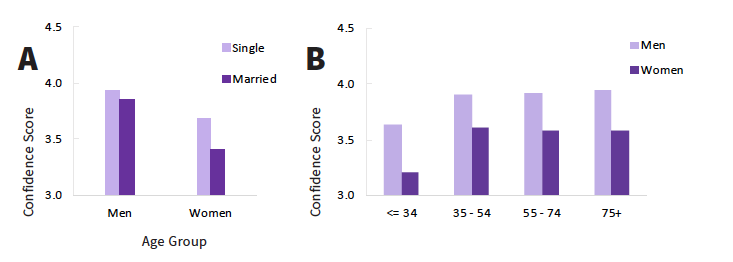

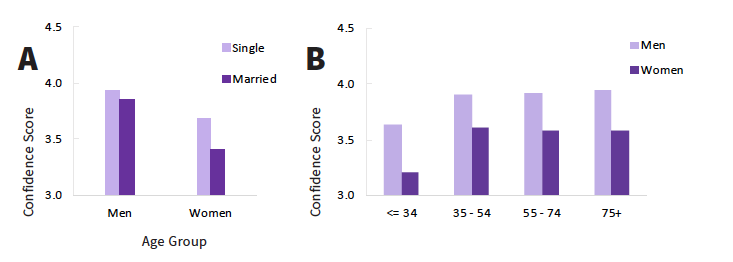

Consistent with our hypothesis, when examining financial confidence as represented by the number of “Don’t know” responses on a financial literacy quiz, we found that, in line with other surveys, women answered “Don’t know” almost twice as often as men (19.4 percent vs. 10 percent). Women also reported less confidence than men in making major financial decisions, such as tax preparation and home loans. Contrary to our first hypothesis, however, we found no gender differences in confidence when making routine decisions, such as making utility bill payments. Compared to men, women reported lower confidence in making major financial decisions but not routine financial decisions, indicating that gender differences in confidence depends on the types of financial decisions being made.

We also found that women reported less confidence than men in making major financial decisions regardless of age group, marital status, and educational attainment. Across gender, the youngest groups were less confident in making major financial decisions than all three older groups. Notably, millennial women (ages < 35) were the least confident of all groups by gender and age (Figures 4.3). And while single women were more confident than married women in making major financial decisions, this pattern was not found in men; both single and married men reported relatively high levels of confidence versus women.

Women feel less confident making major financial decisions than men regardless of marital status and age group

Figure 4.3A Confidence in making major financial decisions by gender and marital status. Note. Covariates: education and age.

Figure 4.3B Confidence in making major financial decisions by gender and age group. Note. Covariates: marital status and education.

2. Distinct from involvement in making major financial decisions, financial confidence will predict higher financial literacy and account for gender differences.

In support of our second hypothesis, women’s lower financial literacy scores were explained in part by their lower confidence in making major financial decisions. This finding holds, controlling for the effect of marital status and age on financial confidence. The same pattern was found when assessing financial confidence in terms of the total number of “Don’t know” responses on the financial literacy quiz. These findings suggest that women’s performance on financial literacy tests likely reflects confidence more than competence. Thus, enhancing financial confidence in making major financial decisions may reduce observed gender gaps in financial literacy assessments and may also optimize financial decision making later in life.

Path B: Involvement in Financial Decision Making

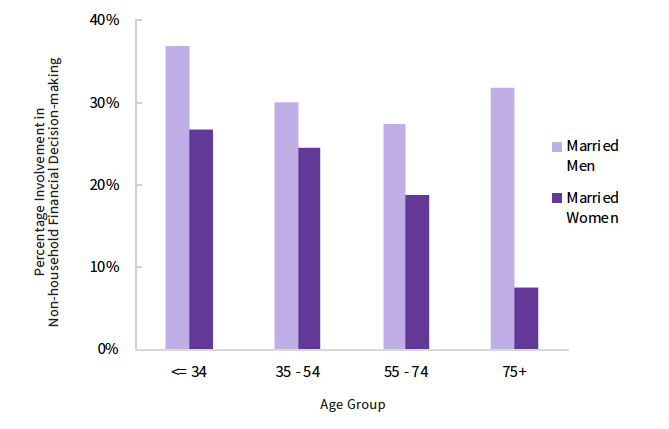

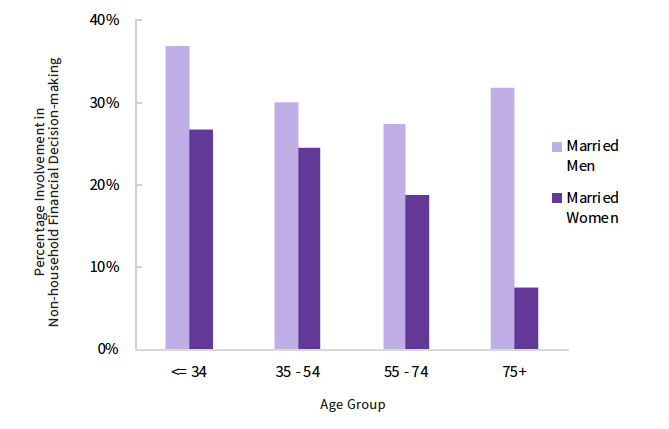

3. Women will be less involved than men in making major financial decisions.

In support of our third hypothesis, we observed gender differences in the level of involvement in financial decision making, which varied as a function of marital status and type of financial decision being made. Not surprisingly, single people indicated that they were the primary decision-maker for most financial decisions regardless of age and gender. Married women, however, were more involved in routine financial decisions than married men across all age groups. In contrast, married men were more involved than married women in major financial decisions (Figure 4.4). As with financial confidence, women’s lower involvement in making major financial decisions versus men was consistent across age groups. Albeit gender differences appear to decline from older to younger age groups in Figure 4.4, this decline was not statistically significant, indicating gender difference to be robust across age groups.

Furthermore, both single millennial men and women (< 35 years) were the least likely of all age groups to be the sole financial decision maker for routine (68 percent vs. 90 percent) and major (70 percent vs. 84 percent) financial decisions. This may be due to a lack of interest or a lack of motivation, but it may also suggest that single millennials are more likely to seek help from others when making any financial decision.

Married women are less involved in making major financial decisions than married men across all age groups

Figure 4.4. Gender differences in involvement in making major financial decisions among married individuals.

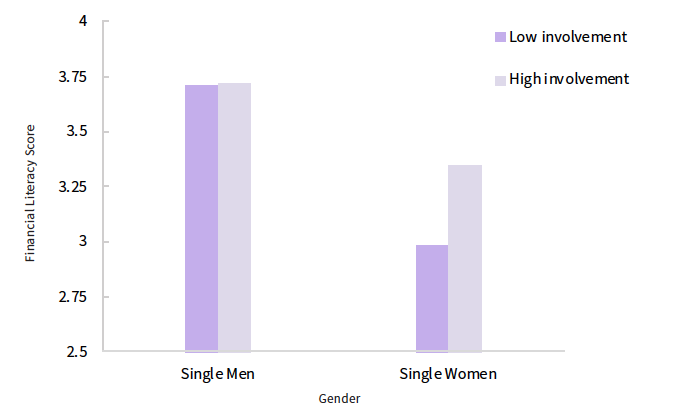

4. Distinct from confidence, involvement in major financial decisions will predict higher financial literacy and account for gender differences.

We found partial support for our fourth hypothesis: Involvement in major financial decisions was positively associated with financial literacy in single persons, but not in married people. Moreover, we only found this effect to be significant among single women. Thus, for single women, greater involvement in making major financial decisions predicted higher financial literacy (see Figure 4.5). This may be because, in contrast to married women, single women are more likely to delegate or attribute financial decision outcomes to themselves as opposed to other people. There was no significant effect of involvement in major financial decisions on financial literacy for single men, indicating that men are relatively more financially literate than women regardless of degree of involvement in major financial decision making. That is, no effect was seen among single men primarily because “uninvolved” men performed as well as “involved” men on the financial literacy test.

Involvement in making major financial decisions predicts higher levels of financial literacy among single women, although they still underperform in financial literacy tests as compared to American men as a whole

Figure 4.5. Gender differences in involvement in making major financial decisions by marital status.

Single women who were highly involved in making major financial decisions still scored significantly lower on financial literacy tests than their highly involved single male counterparts. Yet because involvement in making major financial decisions was associated with higher financial literacy among single women, increasing involvement in major financial decisions may offer an additional route for single women to more effectively learn about finances. If so, women who were not involved in or lack responsibility for making major financial decisions may not benefit as much from financial education as those with real-life experience, whether single or married.

In sum, having confidence in making major financial decisions, instead of in making routine, relatively mundane ones, appears to be especially critical for women to acquire and secure financial knowledge. These findings also show that marital status plays a significant, but distinct role for women versus men in how financial confidence, involvement in making major financial decisions, and financial literacy relate to one another.

Implications for Starting a Long-Term Career

When it comes to making real-world financial decisions, does it actually matter how confident someone is? Many financial decisions made later in life, such as retirement, working, caregiving, and health care, vary by gender. Yet the stage for gender differences in financial decisions is set much sooner in adult life. For instance, career planning can have a significant, lasting impact on financial security throughout someone’s entire life [24, 25]. As people embark on long-term careers in young adulthood, for example, many employers offer sponsored financial benefits, such as health insurance and retirement plan contributions. These benefits typically grow exponentially in value, signifying the importance of starting a long-term career trajectory early in adulthood. The age at which a person starts their career is especially key in light of increased life expectancy, because employer-driven financial decisions can also serve as a catalyst for engagement in other financial decisions outside of the workplace, such as investing and debt management.

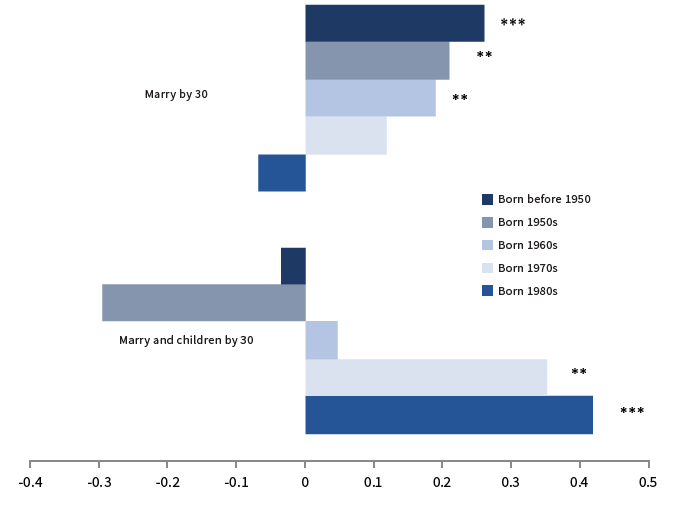

As a follow-up study, we explored possible gender differences in when people start a long-term career and whether financial confidence accounts for these differences. In the same survey as above, participants had indicated whether they had “started a long-term career” and if so, at what age. This measure was part of the Stanford Center on Longevity Milestones survey that measures the ideal and actual ages of achieving various life milestones across the life course. For our study, we assessed the percentage of people who began a long-term career by age 30. We did not specify the length or type of career so that respondents were free to visualize any sort of career they wanted. We included financial literacy, age, education, and marital status as covariates in our analyses.

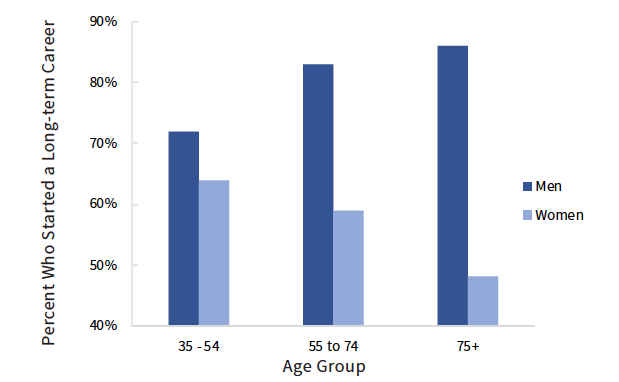

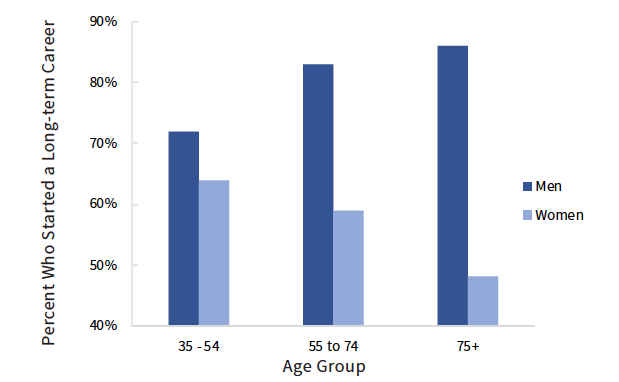

Although gender gaps appear to be diminishing across generations, women over 35 years of age are less likely to have started a long-term career by age 30 compared to men

Figure 4.6. Percentage of individuals who started a long-term career by age 30 by gender and age group.

Key Findings

- On average, men were significantly more likely than women to have started a long-term career by age 30. Gender differences were significant across all age groups but were most pronounced among older generations (Figure 4.6).

- Married and college-educated individuals were more likely to have started a long-term career by age 30.

- The lower likelihood that women would have started a long-term career by age 30 was partly explained by the fact that they had lower confidence in making major financial decisions relative to their male counterparts (Figure 4.7).

Here, we demonstrate the importance of financial confidence in achieving long-term positive financial outcomes. While much of the research on gender differences typically focuses in on longer-range decisions relevant to those in mid to late life, these gaps can emerge at all stages of life across multiple contexts. In the context of career planning, for instance, women over the age of 35 who are less financially confident get started in their careers later than men. We also explored gender differences in planning for retirement by age 30 and found that, in this context, women age 55 and older were less likely to do so compared to men. Yet, women age 35-54 did not differ from men when it came to planning for retirement. This may be because retirement plan decisions are becoming increasingly shaped by organizational policies, helping to reduce some gender inequalities among younger workers.

For many financial outcomes, however, it may be difficult to close gender gaps without first addressing financial confidence. By targeting and raising confidence first, women may feel more capable of making major financial decisions, be more open to learning about financial topics, and be more likely to retain financial information. And as financial confidence grows, financial education programs may be increasingly effective in boosting financial literacy, ultimately helping to optimize financial decisions and financial security throughout the course of an entire life.

Key Takeaways

- Women are much less confident than men when taking a financial literacy assessment and when evaluating how they feel about making major financial decisions, such as investing. These types of major financial decisions are commonly tied to and enhanced by being financially literate.

- For both men and women, higher financial confidence predicts higher financial literacy. The association between these two is likely reciprocal; yet, if financial confidence is indeed a precursor to financial literacy, then issues surrounding financial confidence should be addressed before any benefit can be expected from financial education programs. Increasing financial confidence is of critical importance for women, who are still lagging far behind men regardless of age.

- We should also consider the role of marital status when looking at gender differences in managing financial decisions and the possible impact on promoting financial literacy. Whereas single men and women are equally involved in making financial decisions, we observed a traditional division of labor among married people, with men assuming more responsibility for making major financial decisions and women assuming more responsibility for making routine financial decisions. This division is evident even among young generations. A crucial time to intervene for managing finances may be before women marry and adopt traditional, gendered roles.

- While managing finances appears to be critical for single women’s financial literacy, it doesn’t have the same effect among married women, suggesting that married women are particularly vulnerable and in need of intervention to enhance financial decision making. Yet these findings also suggest that simply encouraging women to get more involved in financial decisions and educating them about finances is insufficient to close the gender gaps in financial security.

- Gender differences emerged throughout the financial decision-making process — from feeling confident about making decisions to being knowledgeable about finances. These differences can affect life choices with important financial consequences. For instance, women who feel less financially confident are more likely to fall behind in starting a long-term career. Intervening early on may be especially impactful in securing a long, financially secure future for women.

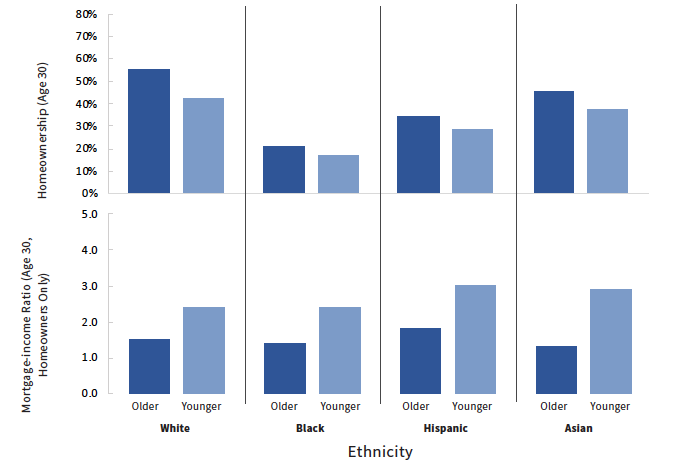

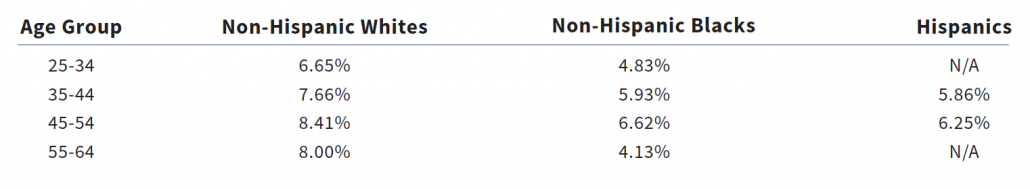

Ethnicity: All American ethnic groups experienced drops in homeownership. Historically, older generations of non-Hispanic whites have had the highest homeownership rate, yet this group has since experienced the largest drop (-13 percentage points). Younger black, Hispanic, and Asians also had a lower homeownership rate than their older counterparts, though to a lesser degree. Across age groups, Asian Americans suffered the least decline of any American ethnic group.

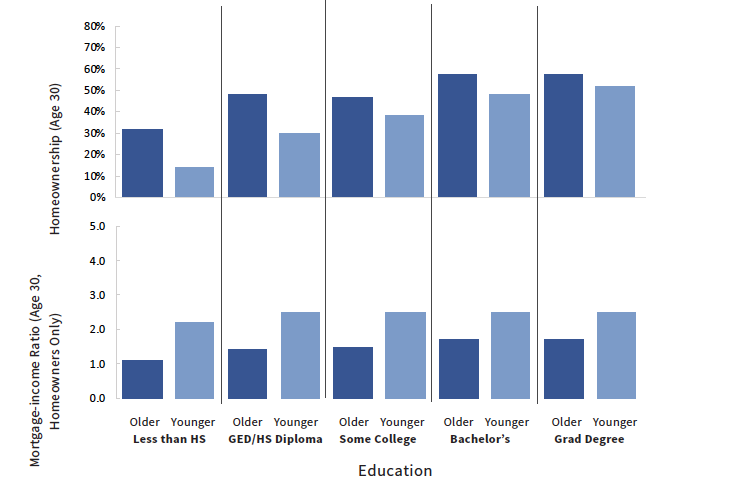

Ethnicity: All American ethnic groups experienced drops in homeownership. Historically, older generations of non-Hispanic whites have had the highest homeownership rate, yet this group has since experienced the largest drop (-13 percentage points). Younger black, Hispanic, and Asians also had a lower homeownership rate than their older counterparts, though to a lesser degree. Across age groups, Asian Americans suffered the least decline of any American ethnic group. Education: Those without any college education experienced the largest drop in homeownership – 18 percentage points. In comparison, the college-educated group had a 9 percentage-point decrease, and those with graduate degrees had only a 5 percentage-point decrease.

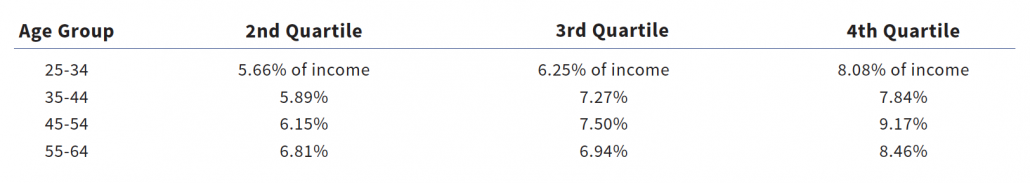

Education: Those without any college education experienced the largest drop in homeownership – 18 percentage points. In comparison, the college-educated group had a 9 percentage-point decrease, and those with graduate degrees had only a 5 percentage-point decrease. Income: Because those with higher income levels in older generations were much more likely to own homes, that income group showed the largest cross-generational drop (third and fourth quartiles: -13 percentage points) compared to those with income below the median. Despite having higher absolute rates of homeownership, the younger cohorts with the highest income have lost the most ground compared to the previous generation.

Income: Because those with higher income levels in older generations were much more likely to own homes, that income group showed the largest cross-generational drop (third and fourth quartiles: -13 percentage points) compared to those with income below the median. Despite having higher absolute rates of homeownership, the younger cohorts with the highest income have lost the most ground compared to the previous generation.

I

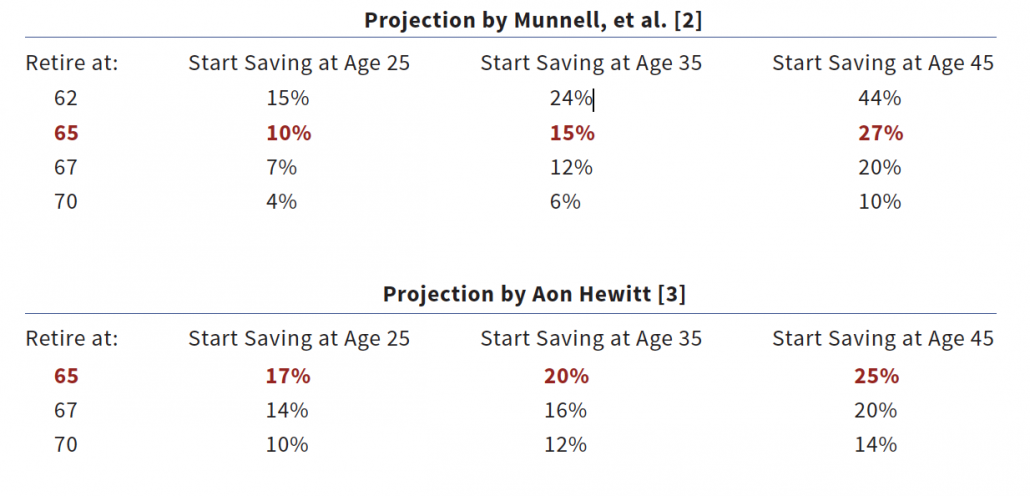

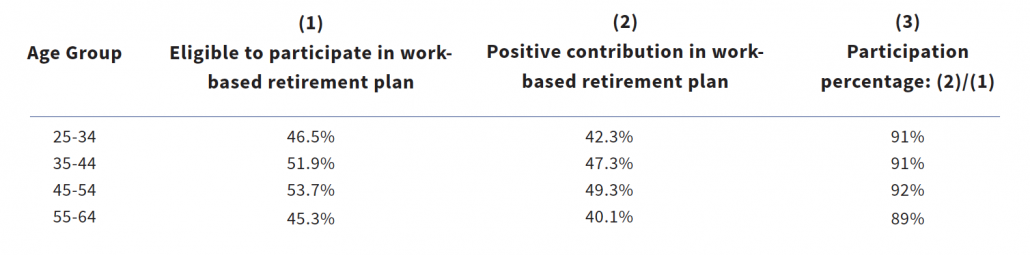

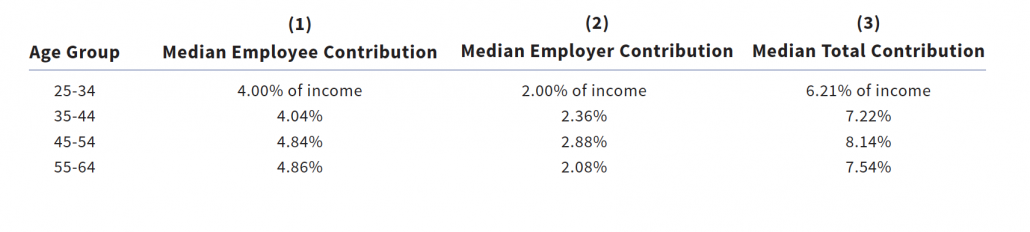

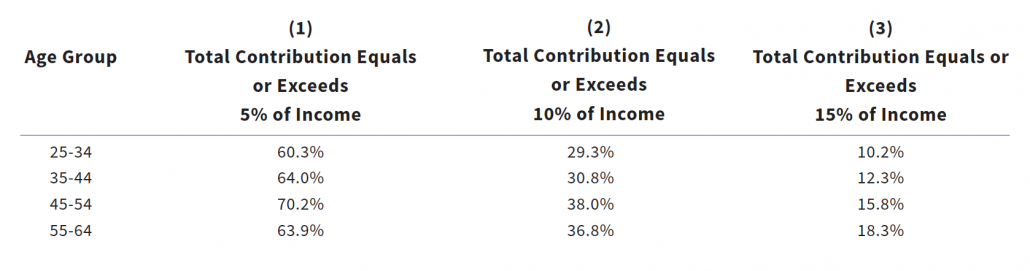

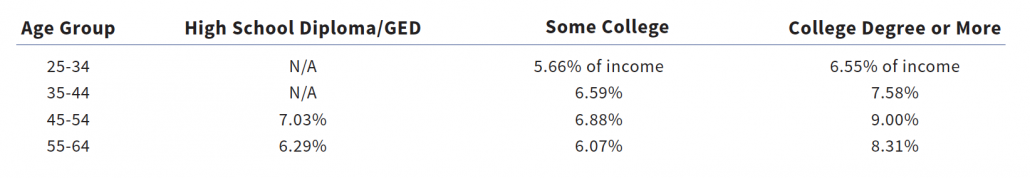

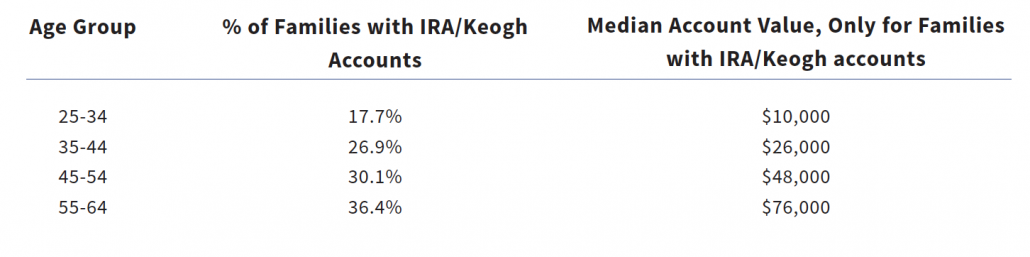

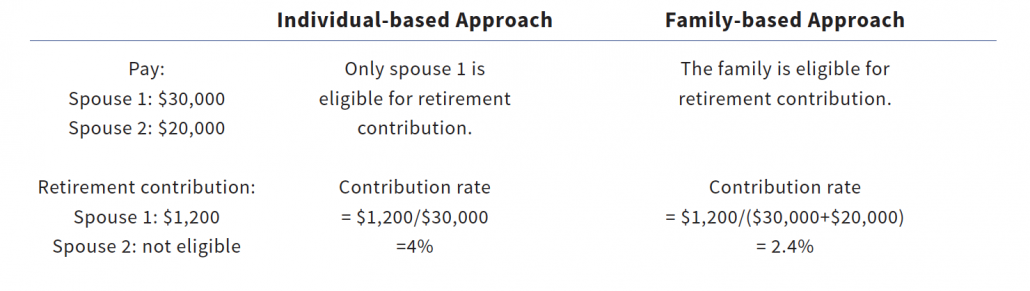

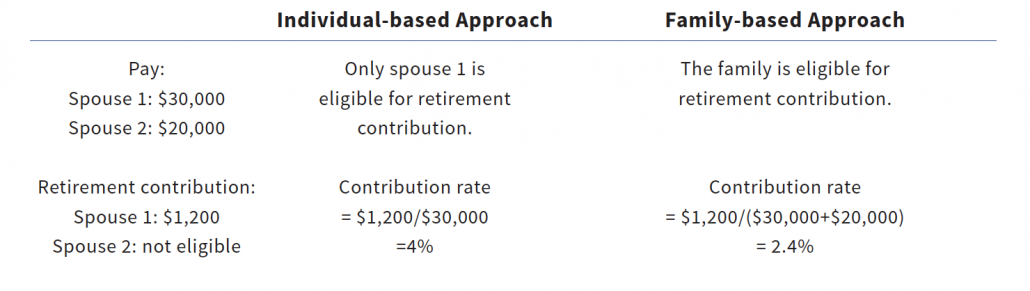

I Does America have a retirement savings crisis? There’s been a lot of heated debate around this question, particularly as members of the baby boom generation enter their retirement years. But the concern extends to younger generations as well. For American working families, what percentage of their income do they need to save for retirement? In the following report, we evaluated the adequacy of retirement savings for American families age 25-64 by examining their retirement plan contribution levels, using the most recent Survey of Consumer Finances

Does America have a retirement savings crisis? There’s been a lot of heated debate around this question, particularly as members of the baby boom generation enter their retirement years. But the concern extends to younger generations as well. For American working families, what percentage of their income do they need to save for retirement? In the following report, we evaluated the adequacy of retirement savings for American families age 25-64 by examining their retirement plan contribution levels, using the most recent Survey of Consumer Finances

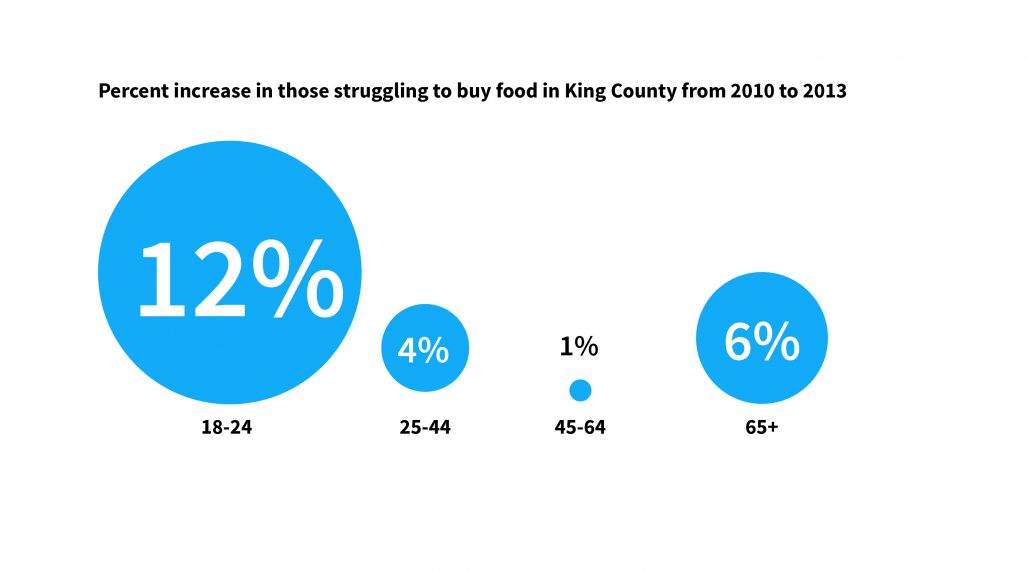

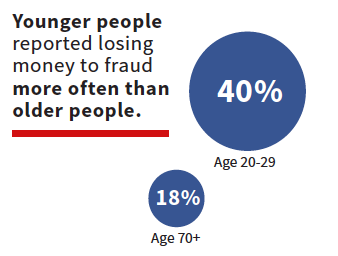

Millions of Americans fall victim to fraud each year, costing upward of $50 billion annually. Nearly everyone is targeted by a scam at some point in their life and many ultimately deceived. Yet, most assume fraud affects only the elderly and see they themselves as invulnerable to being duped. In fact, the Federal Trade Commission finds that adults ages 20-29 experience the highest rates of fraud, whereas those ages 75 and older were victimized the least. This misconception that only the elderly are susceptible to fraud can prevent Americans from taking the necessary precautions to avoid falling victim to financial scams.1

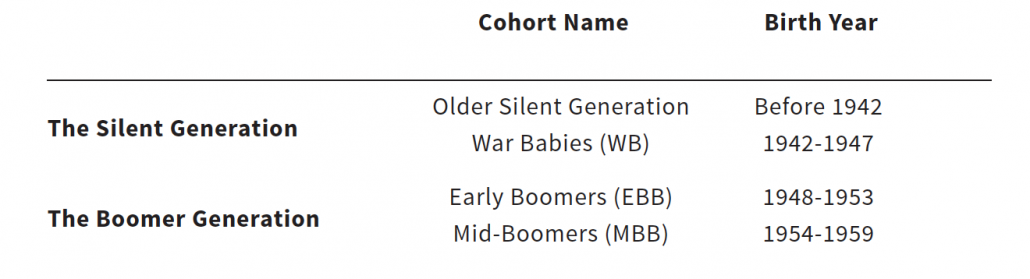

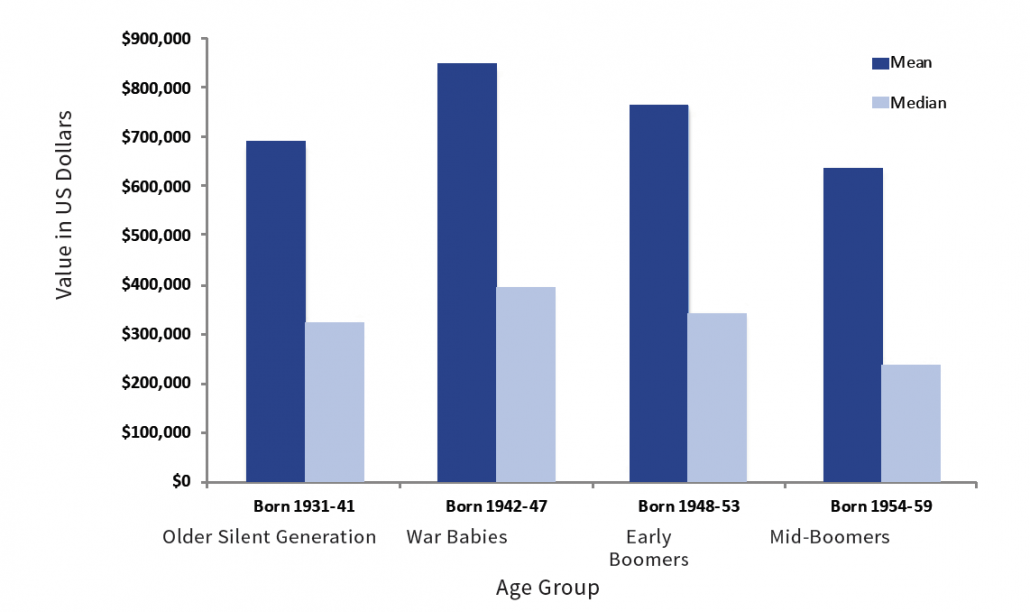

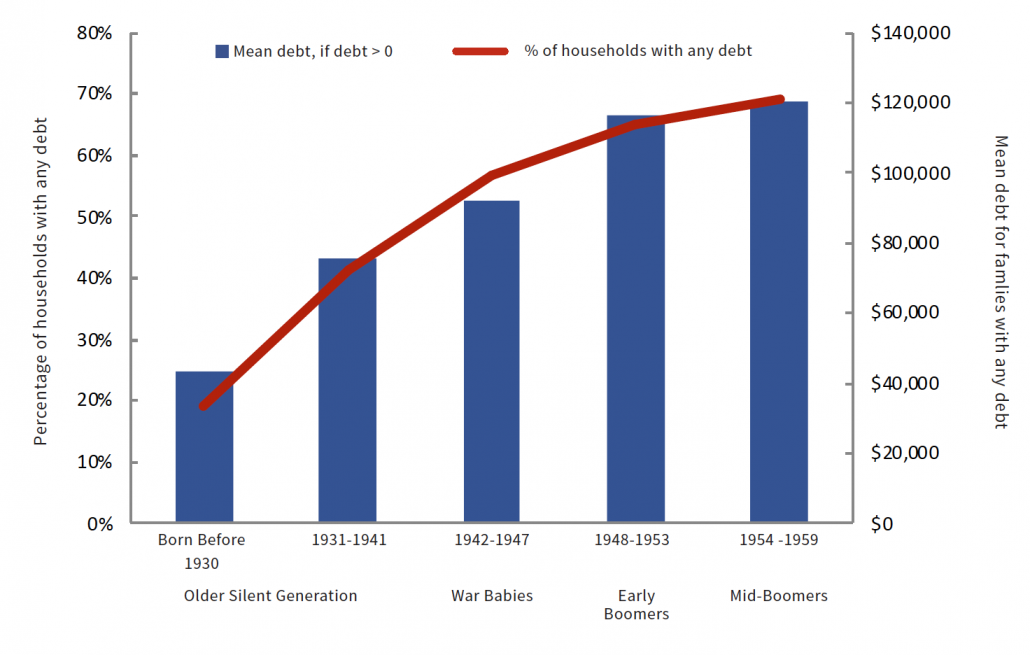

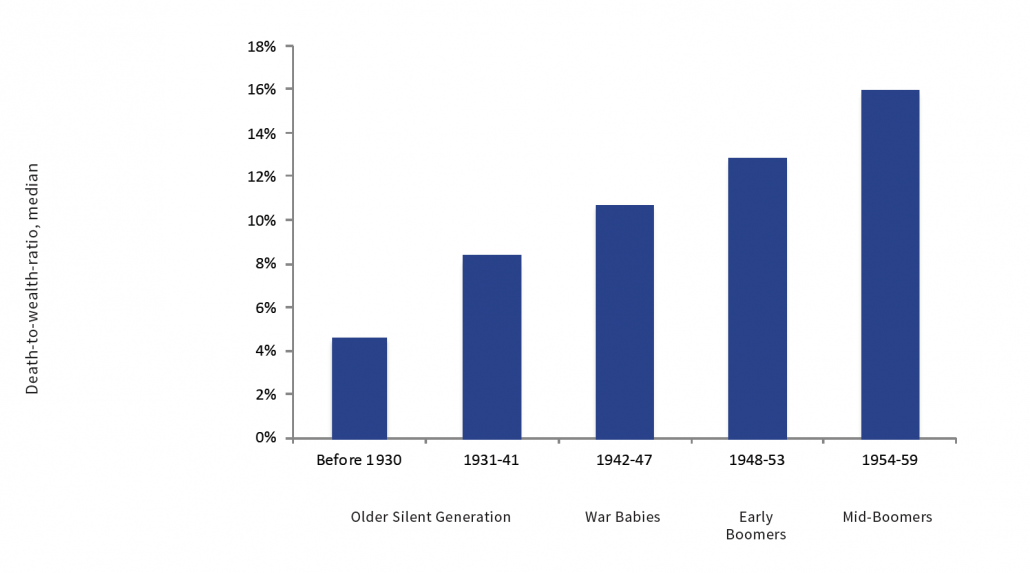

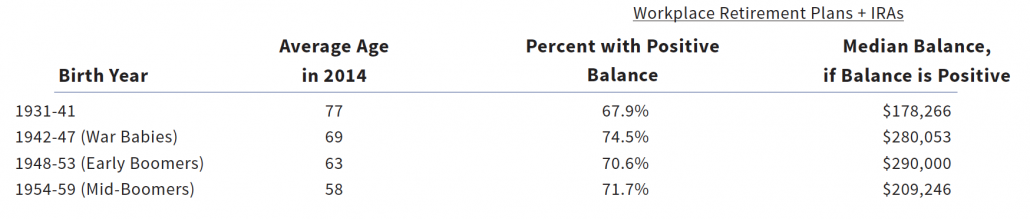

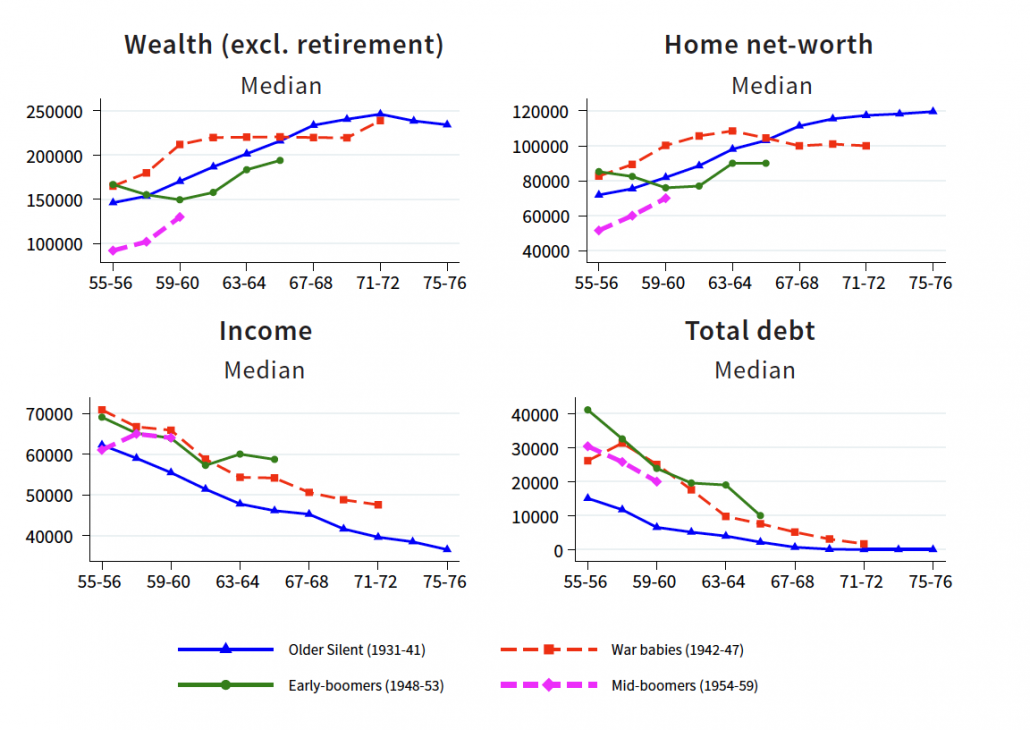

Millions of Americans fall victim to fraud each year, costing upward of $50 billion annually. Nearly everyone is targeted by a scam at some point in their life and many ultimately deceived. Yet, most assume fraud affects only the elderly and see they themselves as invulnerable to being duped. In fact, the Federal Trade Commission finds that adults ages 20-29 experience the highest rates of fraud, whereas those ages 75 and older were victimized the least. This misconception that only the elderly are susceptible to fraud can prevent Americans from taking the necessary precautions to avoid falling victim to financial scams.1 Relative to the working population, U.S. retirees have fewer sources of ongoing income to utilize for their financial needs. They rely primarily on Social Security, employer-sponsored retirement accounts, Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), and, to some extent, their homes. The opportunities to further accrue income-generating assets, such as stocks and bonds, diminish for most people post-retirement. Corresponding to the declining income are growing health costs, which are expected to continue rising to a degree that could be potentially prohibitive for many retirees. In 2013, average out-of-pocket health care spending by Medicare beneficiaries was 41 percent of average per capita Social Security income [1]. Life expectancy in the U.S. has also increased, from 69.7 years in 1960 to78.7 years in 2015 [2]. However, the standard retirement age hasn’t changed accordingly [3], which means that, absent other means, funds have to be stretched across a longer lifespan.

Relative to the working population, U.S. retirees have fewer sources of ongoing income to utilize for their financial needs. They rely primarily on Social Security, employer-sponsored retirement accounts, Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), and, to some extent, their homes. The opportunities to further accrue income-generating assets, such as stocks and bonds, diminish for most people post-retirement. Corresponding to the declining income are growing health costs, which are expected to continue rising to a degree that could be potentially prohibitive for many retirees. In 2013, average out-of-pocket health care spending by Medicare beneficiaries was 41 percent of average per capita Social Security income [1]. Life expectancy in the U.S. has also increased, from 69.7 years in 1960 to78.7 years in 2015 [2]. However, the standard retirement age hasn’t changed accordingly [3], which means that, absent other means, funds have to be stretched across a longer lifespan.

Many people consider financial knowledge to be essential to achieving financial well-being throughout their entire life. Yet, compared to men, women show consistently lower levels of both financial knowledge and financial literacy. Women are similarly at a disadvantage when it comes to achieving financial security. For instance, when examining the cumulative wealth of Americans age 50 years and older [1], older men were shown to have accumulated more wealth than women of the same age by $100,000 or more. Analysis done in the Health and Retirement Study also shows that older women earn significantly less than men of the same age in terms of both salary and pensions (Figure 4.1).

Many people consider financial knowledge to be essential to achieving financial well-being throughout their entire life. Yet, compared to men, women show consistently lower levels of both financial knowledge and financial literacy. Women are similarly at a disadvantage when it comes to achieving financial security. For instance, when examining the cumulative wealth of Americans age 50 years and older [1], older men were shown to have accumulated more wealth than women of the same age by $100,000 or more. Analysis done in the Health and Retirement Study also shows that older women earn significantly less than men of the same age in terms of both salary and pensions (Figure 4.1).

In 2016, the Stanford Center on Longevity released its inaugural Sightlines Project report, which identifies three domains—financial security, social engagement, and healthy living—as being impactful to Americans’ longevity and well-being. In the current and following years, the Sightlines project team, headed by Dr. Tamara Sims, is working on deeper, focused investigations into each of the three domains. The present report is the first of such outputs, focusing on financial security.

In 2016, the Stanford Center on Longevity released its inaugural Sightlines Project report, which identifies three domains—financial security, social engagement, and healthy living—as being impactful to Americans’ longevity and well-being. In the current and following years, the Sightlines project team, headed by Dr. Tamara Sims, is working on deeper, focused investigations into each of the three domains. The present report is the first of such outputs, focusing on financial security.