Gender Differences in Social Engagement and Their Implications for Health and Subjective Wellbeing

Jialu L. Streeter

Jialu L. Streeter

Gender is associated with many social and behavioral differences. Researchers have explored gender-related differences in helping behavior, aggressive behavior, influenceability, and nonverbal behaviors (Eagly, 2013). Analyses of genetics and physiology are also used to help explain the observed gender dissimilarities. For example, one recent study uses brain imaging to explain why boys are more drawn to video games than girls (Dong et al., 2018).

This chapter focuses on gender differences in the domain of social engagement. When considered in the aggregate, men and women appear to diverge in the way they socialize, gain acceptance into peer groups, compete for status within a social structure, maintain friendships, and give and receive emotional support. Such differences have been observed not only among adults but also among young children. Gender dissimilarities are found in the degree to which one views oneself as dependent on others, the size and content of one’s social network, and the giving and receiving of social support. Such gender gaps in social engagement bear essential implications as they may lead to differences in health outcomes and subjective wellbeing.

In a seminal paper (Markus & Kitayama, 1991), psychologists described two different construals of the self – an independent view and an interdependent view. The differences between the two construals largely depend upon what role is assigned to others. For example, for the independent self, others are outside of the boundaries of the self; on the contrary, the interdependent self considers others within the boundaries of the self, and value relations with others as part of the defining features of the self.

The construals of the self, whether independent or interdependent, affect how we perceive relationships with friends and family, the emotions and feelings we exchange with them, and how sensitive and aware we are of others and their needs. The perception of the relative distance of self and others has profound implications for the quantity and quality of social ties.

Gender correlates with the construals of the self. Researchers found that men tend to have an independent self-construal, whereas women tend to maintain an interdependent self-construal. The differences in self-construals help explain many gender differences in cognitive, motivational, emotional, and social behaviors (Cross & Madson, 1997).

Despite the differences in the self-construals, both genders desire the feeling of belongingness. Men tend to seek social connections in a broader group (“tribal”), pursuing their belongingness by competing for power and status; on the contrary, women are more likely to focus on a few intimate dyadic bonds. Men tend to form larger groups organized around specific purposes, whereas women incline to nurture a tight circle of confidants, who they can count on during difficult times (Baumeister & Sommer, 1997; Zunzunegui et al., 2003).

Interestingly, the gender differences in social network inclusion and perceptions of others are manifested in children (Gifford-Smith & Brownell, 2003; Walker, 2010). A study following fourth- and fifth-grade children revealed a stronger “in-group, out-group” phenomenon among males than females (Benenson, 1990). The boys who belonged to a social network enjoyed significantly higher peer group acceptance ratings than girls who were part of social networks. Moreover, when asked to assign attributes to describe same-sex peers, boys were significantly more likely than girls to use words in categories such as academic ability, work habits, strange, athletic ability, interest, artistic, and academic ability. On the contrary, girls were significantly more likely to use words in categories such as nice and reciprocal.

As we shall see in the following sections, the mechanisms through which men and women identify themselves in relation to the surrounding environment affect both the width and depth of their social networks.

Men and women have social networks of similar size (Dunbar & Spoors, 1995; Vandervoort, 2000), but show considerable differences in the content of networks. Women are found to have more kin (e.g., spouse, siblings, children, other family members) and fewer non-kin (e.g., friends, coworkers, acquaintances) in their networks than men (Marsden, 1987; Moore, 1990).

For men and women, a host of predictors, such as employment and education, exert different effects on their network composition. Considering the interaction effect of gender and employment status, researchers found that women, especially those not working full time, manage to maintain close connections to not only more kin, but also more diverse kin types than did men (Moore, 1990). For both genders, more education is associated with a more extensive social network, but for women only, the less-educated live closer to their social circles than the better-educated (Ajrouch et al., 2005).

Studies of a particular type of social network—workplace networks—have shown gender differences in network range, composition, and job leads. The network range demonstrates whether a person has contacts with people from a wide range of occupations. Network composition shows the proportion of a person’s network with high or low work status. Men are found to be more likely than women to know people in more diverse occupations, which gives them an advantage in job search and promotions. For women only, having young children is negatively correlated with both the network range and composition (CAMPBELL, 2016). Given the known importance of weak ties (Granovetter, 1973), the results imply that working mothers with young children may face a particular disadvantage in pursuing career opportunities, as their networks are often too narrow and singular to make vital connections for them.

Sometimes, the same social network channels may bring different career opportunities to men and women. Focusing on American adults in the labor force, researchers have found white men and white women to hold similar social capital (i.e., a combined indicator for network range and composition); however, white men receive significantly more job leads than white women (McDonald et al., 2009). The findings suggest that even when immersed in the same social network infrastructure, seemingly knowing the same people, men and women still retrieve uneven job information and job leads.

Among all people in our social network, we turn to only a small subset of them to exchange deep feelings or to get help. Social support, by definition, is the fulfillment by others of either basic regular needs such as love and affection, confiding, reassurance, and respect, or more intense but time-limited needs such as caregiving after an adverse health shock (Cutrona, 1996). Existing research has demonstrated gender differences in the nature of the support system (Table 1).

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of social relationships | Less intimate Less intense |

More intimate More intense |

| Size of the social support net | Smaller | Bigger |

| Receiving support when needed | Primarily from spouse | From more diverse sources |

| Giving support when needed | Less likely | More likely |

| Internalizing other people’s problems? (e.g., feeling responsible for and trying to solve others’ problems) | Less likely | More likely |

| Emotional towards close relationships | Less intense emotions | More intense emotions |

| Having strong positive feelings (e.g., affection) toward close relationships? | Less likely | More likely |

| Having strong negative emotions (e.g., frustration, conflict, disagreement) toward a close relationship? | Less likely | More likely |

Compared to men, women provide more frequent and more effective social support to others (Belle, 1991), and they generally report having more intimate relationships, of higher quality and more intensity. Such characteristics of women’s social support system have brought both benefits and strains to them (T. C. Antonucci, 2001). When facing challenges, women can amass social supports from multiple resources, relying less heavily than men on the spouse (Gurung et al., 2003; Lynch, 1998). On the other hand, friendships between women tend to be exclusive and intense, with the emphasis placed more often on loyalty, confidence, commitment, and effective aid (Rawlins, 2017). Female socialization prizes conflict resolution and nurturance (Francis, 1997). Women are more likely than men to internalize other people’s problems by taking personal responsibility and finding solutions for their friends and family (T. C. Antonucci, 2001). Being highly involved or overinvested in relationships makes women great sources of support, but also makes them vulnerable to emotional burdens. Maintaining a deep bond, whether with friends or family, can be overwhelming to women. Even though women report having more social support and contacts, which is supposed to reduce depressive symptoms, they also exhibit higher levels of depression than men (Turner, 1994).

Research has shown that, men exchange support primarily with their spouses, whereas women do so with both their spouses and other social connections like friends and children. Figure (1) summarizes some key findings by Antonucci & Akiyama (1987): a higher percentage of men than women receive emotional support, including confiding, reassuring, and respect, from a spouse; however, a higher percentage of women than men receive much emotional support from children. Among those giving social support (not shown in the figure), men are most likely to support their wives, particularly by confiding, talking when upset, and talking about health. A more substantial proportion of women than men offer their children and friends emotional support.

Figure 1: Proportion of people receiving support from different sources (T. C. Antonucci & Akiyama, 1987)

Social participation is defined as an engagement in formal or informal social activities. Formal, structured activities include community meetings, sports, club, political or religious group activities, and volunteering obligations. Informal social activities refer to in-person meetings, phone calls, and other communications with friends or family members not living together.

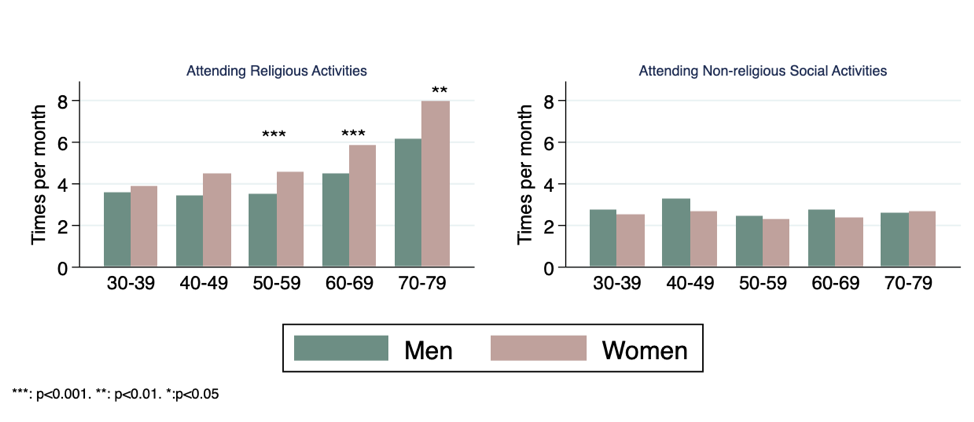

The existing literature doesn’t provide much quantitative evidence on gender differences in social participation across age. Hence, we make use of the Midlife in the United States data to examine whether men and women differ in their involvement in social activities and contacts with social circles. As shown in Figure (2), women are more engaged than men in religious activities,1 but the difference exists only among those over 50 years old. Meanwhile, men and women show similar attendance in non-religious activities, such as professional/union meetings, sport, and social gatherings, across age groups. Neither gender appears particularly involved in non-religious activities, with their attendances hovering around twice a month.

1 For a full discussion of gender orientation in religiosity, see (Francis, 1997).

Figure 2: Women over age 50 attend more religious activities than men of the same age (MIDUS data, author’s calculation)

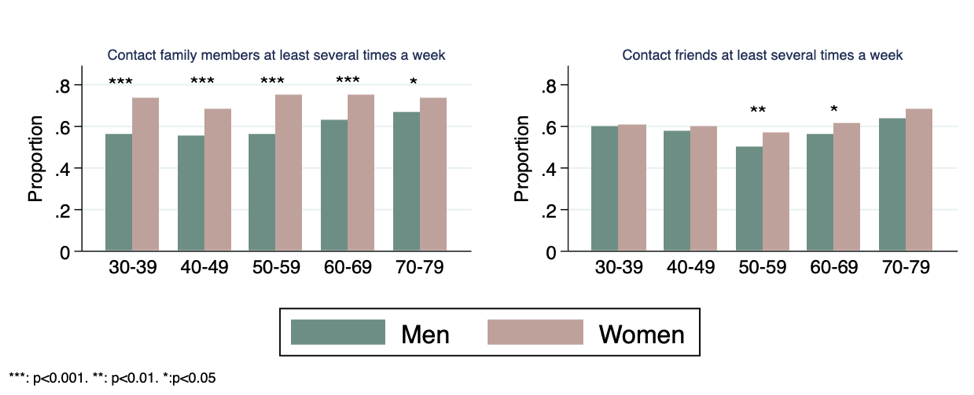

In terms of informal social participation – reaching out to one’s social circle by in-person meetings, phone calls, or emailing/writing, women exhibit a higher level of engagement than men. Women across all ages are more likely than men to maintain frequent contacts with non-cohabiting family members (Figure 3), which is consistent with the previous discussions about women embracing more kin and more diverse kin types in their social network.

Figure 3: Women are more likely than men to contact their family and friends at least several times a week (MIDUS data, author’s calculation)

Many studies have shown the beneficial effects of social integration on reducing premature mortality and improving mental and physical health. However, such protection exhibits varying strength between men and women depending upon the specific social integration measures. As discussed below, for men, it’s marriage and active social participation that shield them most from premature death; for women, it’s high-quality connections that boost their life satisfaction and happiness.

Marriage, involvement in certain social activities, and the network size have shown to have a more substantial beneficial effect on physical health for men than for women (House et al., 1982; Orth-Gomér & Johnson, 1987; Schoenbach et al., 1986). A high level of social activities and outdoor activities has a protective effect against non-cancer mortality for men (Lee et al., 2001).

Men appear to benefit more than women from marriage. Married men consider themselves happier, more satisfied, and less depressed than married women. Widowhood is more devastating, with a strong depressive effect for older men but has a weaker or nonsignificant effect for women (Lee et al., 2001; van Grootheest et al., 1999). Following the death of a spouse, women exhibit considerable resilience and ability to adapt (Wilcox et al., 2003).

Participation in outdoor activities and group activities (e.g., attending voluntary associations meetings, spectator events, classes, or lectures) were found to reduce men’s mortality rate. In contrast, indoor, passive activities such as watching TV were found to be positively associated with mortality. For women, the effect of the activities mentioned above on mortality is either weak or nonsignificant (House et al., 1982).

Instead of focusing on a single health outcome variable like mortality, one can examine a composite of health outcomes. One such measure is allostatic load, which summarizes levels of physiological activity across multiple regulatory systems using indicators such as blood pressure, waist/hip ratio, serum high-density lipoprotein, blood plasma, urinary cortisol excretion, and others. Seeman et al. (2002) found that older men with more social ties and more frequent social contacts were significantly less likely to suffer from a high allostatic load, but the same result doesn’t hold for women.

Other researchers use the Nagi physical functioning scale, which measures a person’s perceived difficulty in performing physical tasks such as pushing/pulling large objects, stooping/kneeling, lifting/carrying 10 pounds, reaching/extending arms, and writing/handling small objects. For both genders, people with more social ties at baseline reported a less functional decline in the following years. Still, the beneficial effect of social relations is more robust for men than for women (Unger et al., 1999).

For women, it’s usually the quality of social support that matters most in shielding them from depression, and lifting their emotional wellbeing, as measured by life satisfaction and happiness.

Women appear to enjoy a higher level of satisfaction if they maintain close, interpersonal relations with others. In contrast, men’s life satisfaction is not strongly associated with their interpersonal relationships with anyone other than a spouse (Cheng & Chan, 2006). Older men report greater satisfaction with marriage than older women, but older women are more satisfied with friends than men (T. C. Antonucci & Akiyama, 1987). Both men and women benefit from more visual contact with relatives, but engagement with friends is protective for cognitive decline in women but not in men (Zunzunegui et al., 2003)

In times of adverse life events such as the death of a spouse, illness, and financial strains, does the lack of social relationships exacerbate people’s levels of depression? Researchers found that in France, Germany, and Japan, women with more negative social relationships exhibit higher levels of depressive affect in times of hardship (Unger et al., 1999). The same results don’t hold for men.

This chapter reviews studies on gender differences in social engagement patterns and behaviors. Gender plays an important role in self-construals, the quantity and quality of the network, and the level of social participation. Regarding the effect of social engagement on health and subjective wellbeing, men and women appear to benefit from different aspects of social integration and connections.

Acknowledgement: We thank Sasha Shen Johfre and Hsiao-Wen Liao for their insights and valuable comments.

Ajrouch, K. J., Blandon, A. Y., & Antonucci, T. C. (2005). Social Networks Among Men and Women: The Effects of Age and Socioeconomic Status. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 60(6), S311–S317. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/60.6.S311

Antonucci, T. C. (2001). Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support, and sense of control. In Handbook of the psychology of aging, 5th ed (pp. 427–453). Academic Press.

Antonucci, T. C., & Akiyama, H. (1987). An examination of sex differences in social support among older men and women. Sex Roles, 17(11), 737–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00287685

Antonucci, T., Lansford, J., Akiyama, H., Smith, J., Baltes, M., Takahashi, K., Fuhrer, R., & Dartigues, J. (2002). Differences Between Men and Women in Social Relations, Resource Deficits, and Depressive Symptomatology During Later Life in Four Nations. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 767–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00289

Baumeister, R. F., & Sommer, K. L. (1997). What do men want? Gender differences and two spheres of belongingness: comment on Cross and Madson (1997). Psychological Bulletin, 122(1), 38–44; discussion 51-55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.38

Belle, D. (1991). Gender differences in the social moderators of stress. Columbia University Press.

Benenson, J. F. (1990). Gender Differences in Social Networks. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 10(4), 472–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431690104004

CAMPBELL, K. E. (2016). Gender Differences in Job-Related Networks: Work and Occupations. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888488015002003

Cheng, S.-T., & Chan, A. C. M. (2006). Relationship With Others and Life Satisfaction in Later Life: Do Gender and Widowhood Make a Difference? The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 61(1), P46–P53. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.1.P46

Cross, S. E., & Madson, L. (1997). Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin, 122(1), 5–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5

Cutrona, C. E. (1996). Social Support in Couples: Marriage as a Resource in Times of Stress. SAGE Publications.

Dong, G., Wang, L., Du, X., & Potenza, M. N. (2018). Gender-related differences in neural responses to gaming cues before and after gaming: Implications for gender-specific vulnerabilities to Internet gaming disorder. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 13(11), 1203–1214. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsy084

Dunbar, R. I. M., & Spoors, M. (1995). Social networks, support cliques, and kinship. Human Nature, 6(3), 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02734142

Eagly, A. H. (2013). Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-role interpretation. Psychology Press.

Francis, L. J. (1997). The Psychology of Gender Differences in Religion: A Review of Empirical Research. Religion, 27(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1006/reli.1996.0066

Gifford-Smith, M. E., & Brownell, C. A. (2003). Childhood peer relationships: Social acceptance, friendships, and peer networks. Journal of School Psychology, 41(4), 235–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(03)00048-7

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. https://doi.org/10.1086/225469

Gurung, R. A. R., Taylor, S. E., & Seeman, T. E. (2003). Accounting for changes in social support among married older adults: Insights from the MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Psychology and Aging, 18(3), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.487

House, J. S., Robbins, C., & Metzner, H. L. (1982). The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: Prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 116(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113387

Lee, G. R., DeMaris, A., Bavin, S., & Sullivan, R. (2001). Gender differences in the depressive effect of widowhood in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(1), S56-61. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/56.1.s56

Lynch, S. A. (1998). Who supports whom? How age and gender affect the perceived quality of support from family and friends. The Gerontologist, 38(2), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/38.2.231

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (n.d.). Culture and the Self.”Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation. 30.

Marsden, P. V. (1987). Core discussion networks of Americans. American Sociological Review, 52(1), 122–131. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095397

McDonald, S., Lin, N., & Ao, D. (2009). Networks of Opportunity: Gender, Race, and Job Leads. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2009.56.3.385

Moore, G. (1990). Structural Determinants of Men’s and Women’s Personal Networks. American Sociological Review, 55(5), 726–735. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095868

Orth-Gomér, K., & Johnson, J. V. (1987). Social network interaction and mortality: A six year follow-up study of a random sample of the swedish population. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40(10), 949–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90145-7

Rawlins, W. (2017). Friendship Matters. Routledge.

Schoenbach, V. J., Kaplan, B. H., Fredman, L., & Kleinbaum, D. G. (1986). SOCIAL TIES AND MORTALITY IN EVANS COUNTY, GEORGIA. American Journal of Epidemiology, 123(4), 577–591. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114278

Seeman, T. E., Singer, B. H., Ryff, C. D., Dienberg Love, G., & Levy-Storms, L. (2002). Social Relationships, Gender, and Allostatic Load Across Two Age Cohorts. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(3), 395. https://journals.lww.com/psychosomaticmedicine/Fulltext/2002/05000/Social_Relationships,_Gender,_and_Allostatic_Load.4.aspx

Social Support and Strain from Partner, Family, and Friends: Costs and Benefits for Men and Women in Adulthood—Heather R. Walen, Margie E. Lachman, 2000. (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2019, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0265407500171001

Turner, H. A. (1994). Gender and social support: Taking the bad with the good? Sex Roles, 30(7–8), 521–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01420800

Unger, J. B., McAvay, G., Bruce, M. L., Berkman, L., & Seeman, T. (1999). Variation in the Impact of Social Network Characteristics on Physical Functioning in Elderly Persons: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 54B(5), S245–S251. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/54B.5.S245

van Grootheest, D. S., Beekman, A. T. F., Broese van Groenou, M. I., & Deeg, D. J. H. (1999). Sex differences in depression after widowhood. Do men suffer more? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 34(7), 391–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270050160

Vandervoort, D. (2000). Social isolation and gender. Current Psychology, 19(3), 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-000-1017-5

Walker, S. (2010). Gender Differences in the Relationship Between Young Children’s Peer-Related Social Competence and Individual Differences in Theory of Mind. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3200/GNTP.166.3.297-312

Welin, L., Svärdsudd, K., Ander-Peciva, S., Tibblin, G., Tibblin, B., Larsson, B., & Wilhelmsen, L. (1985). PROSPECTIVE STUDY OF SOCIAL INFLUENCES ON MORTALITY: The Study of Men Born in 1913 and 1923. The Lancet, 325(8434), 915–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(85)91684-8

Welin, Lennart, Larsson, B. O., Svärdsudd, K., Tibblin, B., & Tibblin, G. (1992). Social Network and Activities in Relation to Mortality from Cardiovascular Diseases, Cancer and Other Causes: A 12 Year Follow up of the Study of Men Born in 1913 and 1923. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979-), 46(2), 127–132. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25567270

Wilcox, S., Evenson, K. R., Aragaki, A., Wassertheil-Smoller, S., Mouton, C. P., & Loevinger, B. L. (2003). The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health behaviors, and health outcomes: The Women’s Health Initiative. Health Psychology, 22(5), 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.513

Zunzunegui, M.-V., Alvarado, B. E., Del Ser, T., & Otero, A. (2003). Social Networks, Social Integration, and Social Engagement Determine Cognitive Decline in Community-Dwelling Spanish Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 58(2), S93–S100. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.2.S93