How to Utilize Stress to Our Advantage

This blog is part of the Stress Management newsletter. If you like this content, sign up here to receive our monthly newsletter!

Our entire lives, we have received the message that stress is bad for us. From the media and medical professionals to our family and friends, we constantly hear that stress is debilitating and should be avoided at all costs. But Stanford University Associate Professor of Psychology Alia Crum, PhD, claims that stress can potentially serve us in our lives as long as we have the right mindset.

“Things happen in our lives that we don’t have any control over, so rather than try to avoid stress, which is inevitable, how about we change how we perceive stress for a healthier outcome?” asks Dr. Crum. “By shifting our mindset from ‘stress is debilitating’ to ‘stress is enhancing,’ we can utilize the stress in our lives to achieve valued ends.”

What are Mindsets and Why Do They Matter?

A mindset is a core belief or assumption about a category, such as our intelligence, bodies, or a particular skill, that orients us toward certain expectations, attributions, and goals.

“Mindsets about stress are the core beliefs we have about the nature of stress—it’s not about the belief about the stressor, such as the exam, the divorce, or the illness,” says Dr. Crum. “Having a ‘stress is debilitating’ mindset can add stress to the stress. People might think, ‘Oh no, this stress will make me sick,’ which only adds more stress to the situation.”

Dr. Crum explains that the mindsets we hold can have self-fulfilling effects. For example, if we have a mindset that we “aren’t good at taking tests,” we might expect to fail an upcoming exam, and often, this belief becomes the outcome.

Dr. Crum says that it’s not “magic” that our beliefs come to fruition. She says that mindsets have self-fulfilling effects in that they determine, very concretely, the following four mechanisms:

- What we pay attention to.

- How we feel and expect to feel.

- What we are motivated to do.

- Our physiological responses to the stress.

Our stress mindset determines how we approach stress, how we make sense of the hardships in our lives, and what we pay attention to. With a stress is debilitating (SID) mindset, one might focus only on the harmful effects, such as the potential to cause insomnia or illness. However, with a stress is enhancing (SIE) mindset, one’s attention may also go to the positives, such as, “What is the lesson here? What skills am I learning? Is there something I can work on within myself? Have I created stronger relationships due to this stressful situation?”

Our stress mindset also determines how we feel. Someone with a SID mindset may feel fearful, threatened, angry, or resentful for the stressor in their lives. Someone with an SIE mindset could still be angry but also have positive emotions by having such thoughts as, “I acknowledge that this is a hard situation, but I will get through this and become stronger for it. This situation is showing me how resilient I am, and I’m proud of myself for how well I’m handling it.”

What we are motivated to do is also determined by our stress mindset. Those with an SID mindset often shut down or lose emotional control. However, those with an SIE mindset are motivated to endure stress to the extent that it may help them stay focused and push them further to achieve their goals.

At the physiological level, research shows that those with an SID mindset have higher levels of cortisol and lower levels of DHEA growth-promoting hormone in their blood. However, those with an SIE mindset have moderate levels of cortisol and higher levels of DHEA growth-promoting hormone. Therefore, our mindset can create changes in our bodies that are measurable in the lab.

“Mindsets are important in that they create our realities,” says Dr. Crum. “I’m not trying to convince people that stress is enhancing and not debilitating—it can be both. But I believe that whichever mindset we choose will influence what happens in our lives through these four mechanisms.”

Research Backing the “Stress is Enhancing” Mindset

Many researchers promote the message that stress is debilitating, however, Dr. Crum and other researchers have shown that stress can improve these three aspects: health and vitality, performance and productivity, and learning and psychological growth.

The health and vitality aspect may come as a surprise since many of us continually receive the message that stress can make us sick. Dr. Crum acknowledges that many people in various situations have experienced adverse health effects due to stress. However, her research shows that there are cases in which the experience of stress makes people physiologically tougher and more resilient.

For example, there are many everyday instances of how stress makes our body stronger. When we lift weights at the gym, the stress on the muscles breaks them down in order to rebuild them stronger. Vaccines work because they stress the immune system, which has to figure out the pathogen and how to deal with it. In both cases, the body becomes stronger and healthier in response to the stressor.

Dr. Crum also says that an SIE mindset may reduce negative symptoms of stress, such as headaches, backaches, rumination, and insomnia.

“I’m not trying to say that stress doesn’t have debilitating effects on our health, but it doesn’t have to, and there’s another side of the story for some people under some conditions,” says Dr. Crum. “The body’s stress response was not designed to kill us; it was designed to boost our body and mind into enhanced functioning, strengthen our immunity, and promote growth at the physiological level.”

Regarding enhanced performance, any athlete or stage actress can attest that the stress of succeeding can improve the quality of their performance. And any procrastinator will say that the pressure of a deadline can make them more productive. This “good” stress is called “eustress” since the effect of the stress is beneficial.

“There is an implication that eustress is a moderate amount of stress, and when the stress becomes ‘too much,’ we go into distress. But I know many people who endure incredible amounts of stress in their lives, and they become stronger for it,” says Dr. Crum. “So rather than putting our energies into figuring out ways to reduce or manage our stress, I believe it is more useful to transform the way we approach stress by changing our mindset.”

Stress also has an immense impact on our learning and psychological growth. “When you go through stressful experiences, there’s a shattering of typical assumptions about life, and in the midst of that, as painful as it can be, are opportunities for learning, change, and discovery,” says Dr. Crum. “So, you can utilize the stressful experience to open your awareness to growth, insight, and wisdom that would not have been there if it weren’t for the stress in the first place.”

How to Change from a “Stress is Debilitating” to a “Stress is Enhancing” Mindset?

In the free, online course, “ReThinking Stress”, Dr. Crum explains three steps to shift one’s mindset from SID to SIE.

1. Acknowledge

When you start to feel stress in the body and mind, acknowledge it by saying, “I’m feeling stress.”

2. Welcome

Rather than resist the stress, we can welcome it because it reveals what is important to us. For example, when tension arises, we can ask ourselves, “Why am I stressed?” For instance, if you feel stress when your child isn’t doing well in school, this reveals that you care about your child’s success. We can use the stressor to help us identify what we value and what brings meaning in our lives—this alone has a beneficial effect on the immune system, according to Dr. Crum.

In the Welcome step, we may also recognize that our typical emotional response may not serve us in getting what we value. For example, if your usual reaction is frustration toward your child when they bring home a poor grade on a test, this may not be the most effective way to motivate your child to improve their performance.

3. Utilize

Instead of our typical emotional response, Dr. Crum invites us to ask ourselves, “How can we utilize the energy from the stressful situation to help us reach our goals?”

With an SIE mindset, we are more likely to channel the physiological stress response, which includes an increase in energy, narrowed focus, and heightened attention in a useful way. For example, rather than reacting with frustration, we can redirect this increased energy and focus to finding solutions to the problems your child is having at school.

Whenever a stressful situation arises, Dr. Crum recommends implementing the Acknowledge, Welcome, and Utilize steps. She also recommends taking the “Rethinking Stress training”, which aims to utilize the power of our mindset to convert the stress we already have into something beneficial. Dr. Crum recommends that we take the course multiple times until the SIE mindset is established and becomes our default perspective on stress in our lives.

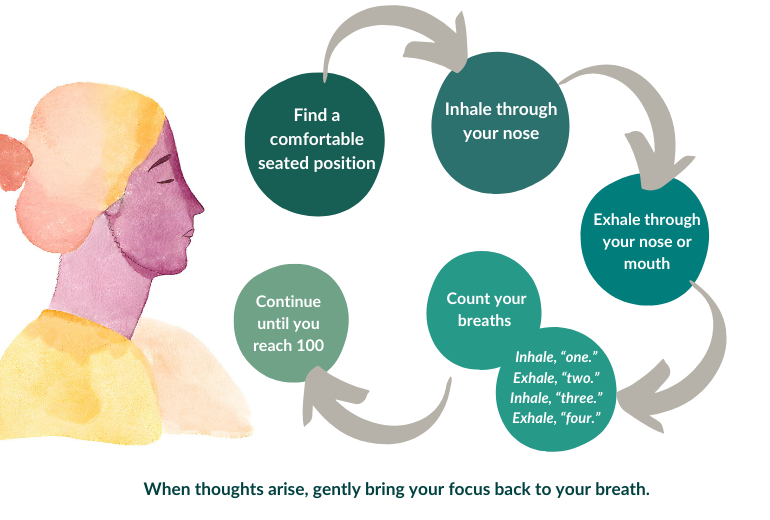

A recent study called Treatments for Anxiety: Meditation and Escitalopram (TAME) compared an 8-week standardized evidence-based mindfulness-based intervention (mindfulness-based stress reduction, MBSR) with medication for the treatment of anxiety disorders. The study included over 200 adults with a diagnosed anxiety disorder that were assigned to either 8 weeks of the weekly MBSR course or taking a medication for anxiety called escitalopram. The MBSR course involved weekly 2.5 hour classes, 45-minuter daily home exercises, and a day-long weekend retreat during the fourth or sixth week. The classes and home exercises involved mindfulness meditation, body scans (directing attention to one part of the body at a time to increase inward awareness), and mindful movements such as stretching. At the end of the 8 weeks, the results showed that the mindfulness program was just as effective at reducing anxiety as medication.

A recent study called Treatments for Anxiety: Meditation and Escitalopram (TAME) compared an 8-week standardized evidence-based mindfulness-based intervention (mindfulness-based stress reduction, MBSR) with medication for the treatment of anxiety disorders. The study included over 200 adults with a diagnosed anxiety disorder that were assigned to either 8 weeks of the weekly MBSR course or taking a medication for anxiety called escitalopram. The MBSR course involved weekly 2.5 hour classes, 45-minuter daily home exercises, and a day-long weekend retreat during the fourth or sixth week. The classes and home exercises involved mindfulness meditation, body scans (directing attention to one part of the body at a time to increase inward awareness), and mindful movements such as stretching. At the end of the 8 weeks, the results showed that the mindfulness program was just as effective at reducing anxiety as medication.