A Director’s Introduction to the 2020 Stanford Longevity Design Challenge

By Ken Smith

Senior Research Scholar

Director, Stanford Longevity Design Challenge

Welcome to the 2020 Stanford Center on Longevity Design Challenge! I’ve had the privilege of directing the Challenge since we first launched the effort in September of 2013. As we enter our seventh year, I’d like to take a few minutes to explain the thinking behind this year’s challenge topic and provide a little (hopefully) helpful advice on how to approach creating an entry.

The process of selecting a challenge topic is not one we take lightly. It generally can be boiled down to three main concerns:

- The topic must be broad enough to encompass potential entries from a range of disciplines and allow for a large number of varying entries. To over-constrain is to limit creativity.

- At the same time, the topic needs to be concise enough to be easily understandable and so that tangible solutions can be envisioned.

- Finally, we try to use the challenge to highlight what we believe are important issues or trends related to longevity. Note that I do not say “related to old age.” Longevity is about what happens over a lifetime and what we all choose to do with the nearly 100 year lives that are becoming increasingly possible. For example, last year’s challenge was about integrational relationships and how to encourage and enrich them. By the very nature of this topic, we asked students to think about multiple generations.

This brings me to our topic this year, “Reducing the Inequity Gap: Designing for Affordability.” I doubt the issue of rising inequality needs much introduction to most of you. It is one of the great issues of our time, as wealth becomes increasingly concentrated in the hands of the few. We see a related dynamic in the longevity innovation space – promising products and services are introduced, but they often only reach the higher economic levels of society, leaving the rest of the population behind. This year we’d like to get you thinking about how to bring the cost of solutions down to a level where everyone can benefit.

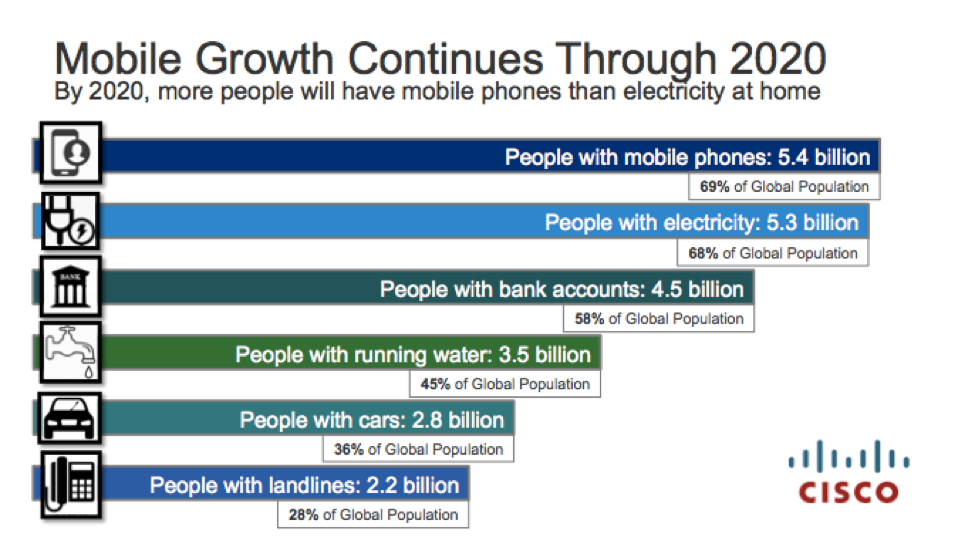

If this idea sounds impossible, I urge you to think about the emergence of cellular phones. These devices were initially considered the height of personal technology and available only to the technically and financially elite. But continued innovation and cost focus has changed this situation drastically. Take a look at the graphic below. A recent study published by Cisco Systems estimates that by 2020 (when we will be holding the Finals for this Design Challenge), more people globally will have cell phones than electricity or running water.

Source: Cisco Systems website: https://newsroom.cisco.com/press-release-content?articleId=1741352, accessed 8/29/19

A key inspiration for this Challenge is a Stanford class called “Design for Extreme Affordability” that is taught jointly by the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design (commonly known as the d.School) and the Stanford Graduate School of Business. Typically focused on solutions for developing economies, design teams in this class work with partner organizations outside of Stanford on radically inexpensive real-world solutions. I urge you to spend time reading through their website at extreme.stanford.edu to understand their process. Their “Projects” page provides a wealth of examples of designs produced in this manner.

In the coming weeks, I will be sharing other examples of great low-cost design, but for now I’d like to share a few things for you to think about as you start down this road:

- Cost is key

In years past, we have included cost as a factor in our judging, but this year we will be putting it front and center. To reflect this, “Affordability” will account for 40% of the judges’ scoring as opposed to 10% previously. See “Judging Criteria” on this site for more details.

- “Affordability”: what does it mean?

We recognize that affordability means different things in different places. What is affordable in a major city in a developed country may be out of reach for those in a rural developing nation. For that reason, we are asking you to go beyond just projecting a cost for your design. We also want you to tell us about your target market and why you believe your solution is affordable in that context.

- Identify the real problem

Unlike years past, we will be considering low-cost versions of existing solutions on an equal footing with new innovations. If you see a product or service on the market that you think you can replace with a lower cost solution, that’s a great potential entry. If you decide to take this approach, you will need to make sure you identify the real problem you are solving. For example, the Embrace project team from Design for Extreme Affordability was trying to reduce infant mortality by designing a lower cost version of an incubator for premature infants. But, they soon realized that the real problem was simply keeping babies warm, which does not need such a complex or resource-intensive product. With this more focused goal, they developed a great solution. Thinking this way early in the process will help open up more possibilities for design.

I want to wish all of you the best of luck in this year’s Challenge. I believe this to be one of our most compelling topics and your solutions could have real impact. If you have questions or comments along the way, you can reach us at [email protected]. I also urge you to follow us on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook as we will be sharing ideas and stories about the Challenge throughout the year.

Happy Designing!

Ken Smith

Senior Research Scholar

Director, Stanford Longevity Design Challenge

Stanford Center on Longevity

Ken Smith joined SCL in July of 2009 as a Senior Research Scholar and Director of Academic and Research Support. He currently is Director of the Center’s Mobility Division. He works closely with SCL’s faculty colleagues to determine where Stanford expertise can best be used to drive change. He brings a broad background of over 20 years of management and engineering experience to his role, including positions in the computing, aerospace, and solar energy industries. He developed a special expertise in working closely with university faculty to develop projects while at Intel, where he was deeply involved in the creation and management of their network of university research labs. He serves on the Advisory Council for AgeTech West. He holds a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Illinois with an M.S. from the University of Washington.

Ken Smith joined SCL in July of 2009 as a Senior Research Scholar and Director of Academic and Research Support. He currently is Director of the Center’s Mobility Division. He works closely with SCL’s faculty colleagues to determine where Stanford expertise can best be used to drive change. He brings a broad background of over 20 years of management and engineering experience to his role, including positions in the computing, aerospace, and solar energy industries. He developed a special expertise in working closely with university faculty to develop projects while at Intel, where he was deeply involved in the creation and management of their network of university research labs. He serves on the Advisory Council for AgeTech West. He holds a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Illinois with an M.S. from the University of Washington.