The Impact of Exercise on Brain Health and Preservation

The foundation of longevity science exists in a balance of healthy physical, mental, and emotional aging. In the past, researchers have studied these aspects of health as independent subjects, but now scientists emphasize that every aspect of our health is intertwined. One of the major motivations behind the Stanford Lifestyle Medicine movement is to increase awareness of how total health is dependent upon the interactions between the pillars of our lives.

Recently, members of the Stanford Lifestyle Medicine team collaborated to conduct a systematic review of existing research on “The Role of Physical Exercise in Cognitive Preservation.” The article, which was published in the American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, responds to a call for more scientific investigations to focus on the prevention of cognitive disabilities associated with old age, such as dementia.

“After conducting this review, a major takeaway is that we should be motivated beyond physical improvements to continue moving our bodies to promote long-term cognitive benefits,” says Matthew Kaufman, MD, lead author of the review article.

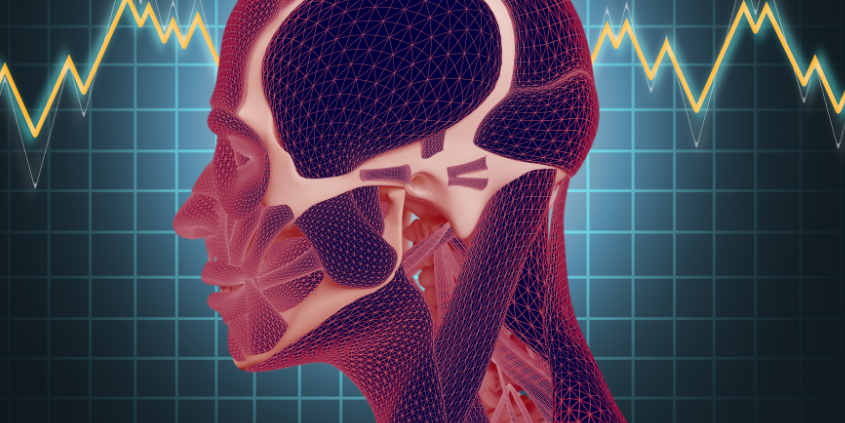

Exercise and the Brain

Both aerobic exercise and strength training are widely researched lifestyle interventions for quality health improvement.The US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) recommends weekly exercise of at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and two days of strength training for improving physical and mental health.

There are multiple proposed mechanisms that define how regular physical activity combats cognitive decay. As you exercise, your heart increases the amount of blood that it pumps out to the rest of the body to compensate for the increased workload. This increase in cardiac output also increases cerebral blood flow, which is linked to heightened neural activity and reduced oxidative stress (or an improved ability to detoxify agents in the body). Another proposed mechanism is the increase in trophic factors (proteins that aid cell survival and growth), such as BDNF, VEGF, and IGF-1. These trophic factors support neuroplasticity (the structural reorganization of the brain to support learning) and angiogenesis (the growth of new blood vessels). Therefore, it is reasonable to promote exercise as a lifelong tool for optimizing brain health.

“It is important to understand the physiology of this relationship in order to maximize exercise regimens for prolonged cognitive benefits and goal setting,” says Dr. Kaufman, current Stanford Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Resident.

Key Takeaways from the Systematic Review

After reviewing over 1,600 total studies, 17 met the team’s final criteria for further analytical evaluation. To be included in the final review, studies must have been a randomized controlled trial published after 2000, excluded cognitive impairments more severe than moderate diagnoses, and included at least one physical activity intervention that lasted for 12 weeks or more and followed the USDHHS recommended guidelines. For this review, both aerobic exercise and strength training were included as exercise interventions. The final 17 studies selected for “qualitative synthesis” looked at the relationships of exercise and global cognition, exercise and memory, and exercise and executive function.

The review team found the largest consensus in the research for improvements in memory for individuals with moderate, mild, or no cognitive impairments following the 12-week exercise interventions. For individuals with mild cognitive impairments, exercise was shown to improve cognition. Although weaker, there was also evidence found for relationships between regular exercise and improved global cognition and executive functioning. Some studies also found significant associations between improvements in physical and cognitive fitness and increases in regional brain volume or blood flow.

However, included studies that analyzed the lasting effects of exercise following the study indicated a need for continued exercise. Improvements in memory and cognitive health were not always maintained once regular exercise stopped. This suggests the importance of exercise as a long-term principle of lifestyle medicine for adequate prevention of late-stage diseases.

“Given that our review demonstrates that people did not see lasting benefits after stopping their exercise, the importance of routine exercise to continue reaping benefits is suggested,” says Dr. Kaufman. “It also strengthens our association that exercise interventions can, in fact, improve cognition.”