Stop The Clock: The Shocking Truth About Age-Related Muscle Loss and Steps to Fight Back

As a physician specializing in peri-operative medicine, I have witnessed firsthand the detrimental impact of muscle loss on patients. Whether it is individuals presenting with hip or spine fractures, or those who have suffered from bleeding in their brain following a fall, many of these acute conditions have a hidden underlying cause: the loss of muscle mass.

Although losing muscle may not seem like a significant concern, it can be a silent yet deadly issue that progressively drains our vitality and strength, leading us to become frail and dependent.

In this blog, we will explore the latest scientific research on the trajectory of muscle loss as we age and discuss practical steps that we can take to prevent or alleviate its effects.

Understanding Skeletal Muscle: Composition and Function

Skeletal muscle is the type of muscle tissue that we can control voluntarily, such as when we intentionally flex our biceps or perform other movements. It is composed of many smaller bundles of muscle fibers, each containing hundreds to thousands of individual fibers. These fibers are primarily made up of two proteins: myosin and actin, which work together to facilitate muscle contraction.

The muscle fibers themselves are arranged in a specific pattern, extending the muscle’s length between the tendinous ends, and are bundled together and wrapped in connective tissue. This arrangement allows the muscle to generate force and produce movement when it contracts.

In terms of composition, muscle tissue is approximately 70% water and 30% protein. The body synthesizes muscle protein from the amino acids that are present in the protein we consume through our diet.

Image credit: University of Miami: https://www.bio.miami.edu/dana/360/360F18_15.html

As we age, the gradual decline in muscle mass and strength worsens with each passing decade. This decline can be attributed to several factors, including reduced dietary protein intake, decreased physical activity, a decline in hormone levels, chronic inflammation, muscle denervation, mitochondrial dysfunction, infiltration of fat into muscle, and insulin resistance.

Research suggests that the rate of loss of muscle strength is greater than the loss of muscle mass and plays a crucial role in healthy aging. When low muscle mass and function, including strength and physical performance, occur with aging, it is known as sarcopenia. The term “sarcopenia” originates from the Greek words “sarx,” meaning flesh, and “penia,” meaning loss.

Sarcopenia can be classified into two categories: primary sarcopenia, which is the cumulative result of various factors leading to muscle loss with aging, and secondary sarcopenia, which is caused by a specific insult, such as surgery, hospitalization, or injury. By understanding these categories, we can better diagnose and manage sarcopenia in older adults.

The trajectory of age-related muscle loss

The loss of muscle strength with age can be surprising to many people, as it can start as early as age 30. As numerous research studies have shown, the rate of decline for muscle mass with age worsens with each decade.

| Age | Percent loss of muscle mass/decade |

| 50s | 0.5-2% |

| 60s | 4-5% |

| 70s | 7-8% |

The decline in muscle strength is more dramatic and can be 2-5 times greater than decline in muscle mass.

| Age | Percent loss of muscle strength/decade |

| 50s | 3-4% |

| 60s | 9-10% |

| 70s | 11-12% |

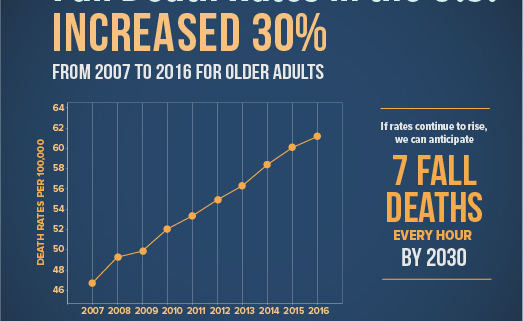

A study found that there was muscle loss of between 35% and 40% occurring between the ages of 20 and 80. Additionally, studies of nursing home residents have found that sarcopenia, affects 30-40% of individuals. Mobility aids, such as canes, walkers, or wheelchairs, are commonly used by older adults, with 24% of those aged 65 years and older relying on such aids. Alarmingly, the death rate from falls is projected to rise sharply in the coming years, as shown in the graph below.

Image Credit: CDC:

Skeletal muscle mass is shown to be an independent predictor of death, highlighting its crucial effect on longevity.

These statistics don’t consider the sudden health events that can accelerate muscle loss. A rapid decline in muscle mass and health occurs with hospitalizations and illnesses. In addition to the lack of activity during hospital stays, other factors like increased levels of pro-inflammatory agents and cortisol can have a compounding effect. For older adults, this loss of muscle mass and function can lead to permanent disability or even death.

Connection between muscle health and dementia

Dementia affects more than 55 million people worldwide, and physical inactivity is one of the modifiable risk factors for the condition. There is a well-established link between low muscle mass, low physical activity, and cognitive impairment in old age.

Exercise releases myokines from the muscle, which crosses the blood-brain barrier and helps regulate BDNF, a protein that supports the survival and growth of neurons in the brain. Furthermore, the lower an individual’s muscle mass, the more significant their cognitive decline, suggesting a dose-dependent effect.

Steps to preserving muscle health and function.

Protecting your muscle mass is like increasing your savings: the greater the savings, the more comfortable you will be as you age.. While we might develop pharmacological treatments for muscle loss in the future, currently, the best way to preserve muscle function is to put in work upfront.

1. Strength training, “the medicine”

Resistance training activates our DNA to respond to stress, leading cells to produce increased muscle protein.

Initially, we may see an improvement in strength but not much muscle hypertrophy because of an increase in muscle protein breakdown. However, this slows down after about six weeks, and we start seeing an increase in muscle size.

Strength training can counteract the accumulation of fat in the muscle, improve the health of neuromuscular junctions, improve muscle quality, and reduce inflammatory markers.

People who do regular resistance training have a 20-year advantage. For example, 85-year-old weightlifters showed similar power and muscle features as 65-year-olds who did not engage in regular training in studies.

To achieve optimum improvement in muscle mass and strength, we should engage in resistance training 2-3 times per week per muscle group in addition to any aerobic exercises.

Resistance exercises that involve increasing load and speed should be done under supervision to ensure proper form and avoid injury.

2. Protein intake

Studies have shown that higher protein intake is associated with greater muscle mass and lower risk of developing frailty in older adults.

Protein intake should be individualized based on age, sex, activity level, and health status, but generally range from 1.6-2.2 grams per kilogram of body weight per day.

A systematic review and meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Nutrition in 2020 found that plant-based protein sources can be just as effective as animal-based sources for improving muscle health. It’s best to mix and match various plant-based sources of protein for optimum effect.

Consuming more than 35-50 grams of protein at one time does not provide any additional benefit for muscle growth, as excess protein is used for energy production. Therefore, it is best to spread protein intake out throughout the day rather than consuming the whole day’s amount in one sitting.

3. Supplements: Please see an excellent blog by Dr. Kaufman on this website to gain more knowledge about the safe use of supplements.

4. We all know to get good sleep and stay hydrated—more on these topics in future blog posts.