Passive and Active Design Approaches

By Ken Smith, Senior Research Scholar and Director, Mobility Division

“Good design is obvious. Great design is transparent”

– Joe Sparano, Design Lecturer at the University of Washington

As discussed in my last blog, the first step in creating a behavioral change product or service is to determine the target behavior and what it is that you want to encourage. A good next step would be to next decide if you want to target an active or passive design. I want to take a little time today to describe the two approaches and show a few examples of how each works.

As discussed in my last blog, the first step in creating a behavioral change product or service is to determine the target behavior and what it is that you want to encourage. A good next step would be to next decide if you want to target an active or passive design. I want to take a little time today to describe the two approaches and show a few examples of how each works.

Active designs are those in which the user is explicitly directed to do (or stop doing) an activity. For example, at the launch of the Apple Watch, CEO Tim Cook warned (somewhat hyperbolically) that “sitting is the new cancer” in response to a number of studies linked extended sedentary behavior with a range of bad health outcomes. To address the issue, Apple included a feature in the watch that directs its users to stand up at 50 minutes past after every hour. It’s a very basic approach, but responses have generally been positive. For a more on the feature, check out this article in Forbes.

Most “reminder apps” fall into this category, along with solutions that rely on coaching. Many people pay for personal trainers to set for themselves a commitment to exercise that includes another person who will actively engage them to show up and to work hard – “You can do it! Push through the pain!” In this case, it is precisely the active part of the intervention that makes it work.

Passive designs, on the other hand, sit in the background and provide a subtle – or even unconscious – nudge. One of my favorite examples of a passive design is the “piano staircase”. First implemented in the Odenplan underground station in Stockholm (I think – the origins are not completely clear), the design encourages people to take the stairs instead of the escalator by turning the stairway into a giant piano keyboard that plays music as people walk up and down.

Passive designs, on the other hand, sit in the background and provide a subtle – or even unconscious – nudge. One of my favorite examples of a passive design is the “piano staircase”. First implemented in the Odenplan underground station in Stockholm (I think – the origins are not completely clear), the design encourages people to take the stairs instead of the escalator by turning the stairway into a giant piano keyboard that plays music as people walk up and down.

This particular installation was created as part of “The Fun Theory”, a project sponsored by Volkswagen to encourage designs that change peoples’ behavior for the better using “fun” as the motivator. For more examples, check out their website.

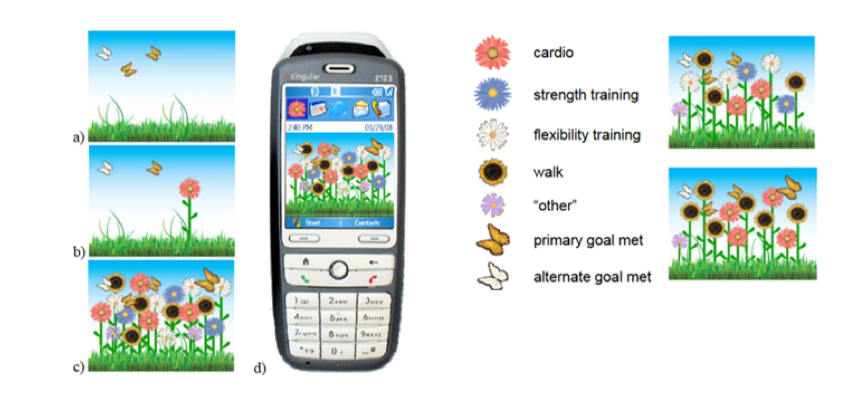

Ref: Consolvo, S., Klasnja, P., McDonald, D.W., Avrahami, D., Froehlich, J., LeGrand, L., Libby, R., Mosher, K., Landay, J.A.: Flowers or a robot army? Encouraging awareness & activity with personal, mobile displays. In: Proc. Ubicomp 2008, pp. 54–63. ACM Press (2008)

Another particularly interesting version of passive design is the ambient display. The idea is to present “at-a-glance” information to users on displays present in their environment. These could be on their smartphone home screen, their refrigerator, or in any number of other locations. The displays provide instant status, which in turn acts as a reminder. For a great description of how this works, I’d recommend reviewing this paper describing development of the “UbiFit” system at Intel Research Seattle. Sunny Consolvo and her colleagues developed an early system to give users an indication of their progress toward activity goals that featured a virtual garden that flourished during weeks of activity – and that remained barren during slow periods.

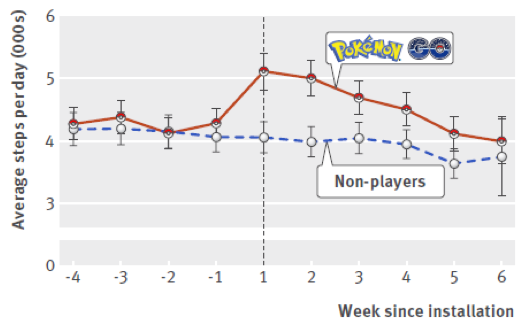

Average number of daily steps and 95% confidence intervals by weeks before and after installation of Pokemon Go (median July 8, 2016) Ref: Howe Katherine B, Suharlim Christian, Ueda Peter, Howe Daniel, Kawachi Ichiro, Rimm Eric B et al. Gotta catch’em all! Pokémon GO and physical activity among young adults: difference in differences study BMJ 2016; 355 :i6270

In both active and passive design approaches, a major problem to consider is one of persistence. It is one thing to get someone to change behavior in the short term – it is quite another to make this change “stick”. We saw a recent example of this on a massive scale in the recent Pokemon GO craze. For those of you who were unconscious during that time, Nintendo released the augmented reality game on July 6th, 2016 and had much of the population walking up and down streets in search of Pikachu and his friends. For a brief moment, physical activity advocates rejoiced as average daily step counts for players increased by 20-30% and many praised the power of gamification. Unfortunately, they were disappointed five weeks later when step counts returned to baseline.

This leads naturally to the question “What turns a behavior into a habit?” That is really a key part of this year’s challenge and something we will be diving into in some depth in future blogs. For now, think about what behavior you want to affect and if you want to do this by direct interaction (active design) or by building features into the users’ environment (passive).

NEXT: Learning about habit formation

Ken Smith joined SCL in July of 2009 as a Senior Research Scholar and Director of Academic and Research Support. He currently is Director of the Center’s Mobility Division. He works closely with SCL’s faculty colleagues to determine where Stanford expertise can best be used to drive change. He brings a broad background of over 20 years of management and engineering experience to his role, including positions in the computing, aerospace, and solar energy industries. He developed a special expertise in working closely with university faculty to develop projects while at Intel, where he was deeply involved in the creation and management of their network of university research labs. He serves on the Advisory Council for AgeTech West. He holds a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Illinois with an M.S. from the University of Washington.

Ken Smith joined SCL in July of 2009 as a Senior Research Scholar and Director of Academic and Research Support. He currently is Director of the Center’s Mobility Division. He works closely with SCL’s faculty colleagues to determine where Stanford expertise can best be used to drive change. He brings a broad background of over 20 years of management and engineering experience to his role, including positions in the computing, aerospace, and solar energy industries. He developed a special expertise in working closely with university faculty to develop projects while at Intel, where he was deeply involved in the creation and management of their network of university research labs. He serves on the Advisory Council for AgeTech West. He holds a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Illinois with an M.S. from the University of Washington.